Gloom abounds

I recently wrote about the gloom surrounding the higher education sector and noted that every day brings new stories about planned cuts to courses and disciplines or redundancy programmes at one university or another. There is a litany of woes, from the declining value of frozen home fees and growing maintenance backlogs to uncertainties around international student recruitment and government targeting of ‘low quality courses’ and ‘rip off degrees.’ Everything seems to be looking bad all over the place and there is much talk of universities being on the edge of bankruptcy.

As noted before though, despite all of these challenges, universities still do a fantastic job, providing outstanding higher education to many hundreds of thousands of students and undertaking world-changing research activity which adds huge value to the economy and society.

Nevertheless, there is real and widespread concern about the precarious position of the sector overall.

You think you’re gloomy?

Glen O’Hara, writing in Prospect in early June, offers a characteristically pessimistic analysis of the current state of higher education and presents this distinctive comment on where we are now:

British higher education is like the Titanic after it had hit the iceberg. It is fatally flawed below the waterline, but it is still floating, and many passengers have difficulty believing that it will go under. Yet the water is pouring in and rising. It has gushed right up past third class, flowed through second class and is about to lap at the doors of first class. During the next parliament, the lights will go out and the ship’s keel will break.

It doesn’t get much more downbeat than that.

Some grounds for optimism?

It’s not all doom and gloom though. David Kernohan, writing on Wonkhe about recent research from the King’s College Policy Institute on public perceptions of universities noted that – and we really shouldn’t be quite as surprised as we are about this – peoplereally do quite like universities:

Three in ten would describe UK universities as “among the best in the world”, with only the royal family, the armed forces, and the NHS polling better among a national representative panel (n=2,683, fieldwork between 1 and 9 May).

Breaking that down a bit – 47 per cent of the sample were broadly positive (7 to 10 on a 10 point scale) about universities in 2024, down from 54 per cent in 2018. Active negativity has risen from 10 to 14 per cent.

And – crucially – seven in ten people (68 per cent) would be concerned by mass university closures, with 61 per cent blaming the UK government, though this slants towards Labour.

It’s possibly good news then that people would be upset if universities started closing down. Many of us in the sector would be more than a little concerned and we know that any closures would be extremely problematic for everyone for all sorts of reasons. Disorderly exits would be massively challenging, messy and expensive to manage. The consequences of such collapses for students, employees, alumni, stakeholders, the towns in which they are anchor institutions and indeed the sector as a whole would be huge.

Mergers may yet emerge as the way forward. There has been much talk of them over the years as the salvation for cash-strapped institutions. But the numbers of them have in reality been small and where they have succeeded it has been because of shared strategic alignment, significant size differential or additional resources being allocated rather than as a way out of a shared crisis. Maybe though if things get really, really bad this will become more commonplace in the sector.

To the rescue?

As reported in THE, the Shadow Education Secretary, Bridget Phillipson has said that stabilising the financial position of the English HE sector will be a “day one” priority should Labour win the election. According to THE she signalled a very different tone and approach to the current government

Asked by Laura Kuenssberg on her BBC Sunday morning show on 23 June whether Labour would use taxpayers’ money to bail out a university that might otherwise go under, Ms Phillipson said: “Universities are in crisis, and I am really concerned about that…I think we do have to tread with real care here because universities right across our country, in our towns and cities, are really important engines of growth and opportunity and jobs.

In the same THE piece it is noted that Labour’s manifesto:

also signalled that it would hold a review of the entire tertiary education sector but this could potentially take several years and university leaders have been pushing it to put stop-gap measures in place, given the number of institutions facing large deficits.

Ms Phillipson refused to be drawn on what measures the party was considering but said universities should expect a different approach should the party win the 4 July election.

It might be then that change under Labour would be more rapid than previously thought.

Review, Review, Review

I’ve argued before that we need a new review of higher education but it felt that one was not likely, at least for a few years. However, the Labour manifesto reference and Phillipson’s comments suggest things may move a little faster

Alistair Jarvis, writing on Wonkhe, offered some helpful analysis of the Labour manifesto and what it might mean for the sector. In particular, quoting from the manifesto, he noted this about the possibility of a review:

‘Skills shortages are widespread. Young people have been left without the opportunities they need. The result is an economy without the necessary skills, nor any plan for the skills needs of the future. Labour will address this by bringing forward a comprehensive strategy for post‐16 education.’ This is a strong hint that we will see a major tertiary education review in the first term of a Labour government. My guess is that this will be launched alongside a spending review in 2025. In terms of the purpose of Higher Education, the manifesto is consistent on two pillars – driving opportunity and driving the economy.

A big review covering all of the challenges and issues of higher education would be a sizeable project indeed. One seeking to address all aspects of tertiary provision would be a blockbuster.

I do think we need a review, a proper and serious one with qualities common to some of the big previous higher education reviews by Robbins, Dearing and Browne. But the impact and resonance of HE reviews has progressively lessened over the years and the half-life of the Higher Education review has shortened (it’s almost like Augar has already been forgotten). So will this one be any different? We have to hope so.

Dealing with the legacy

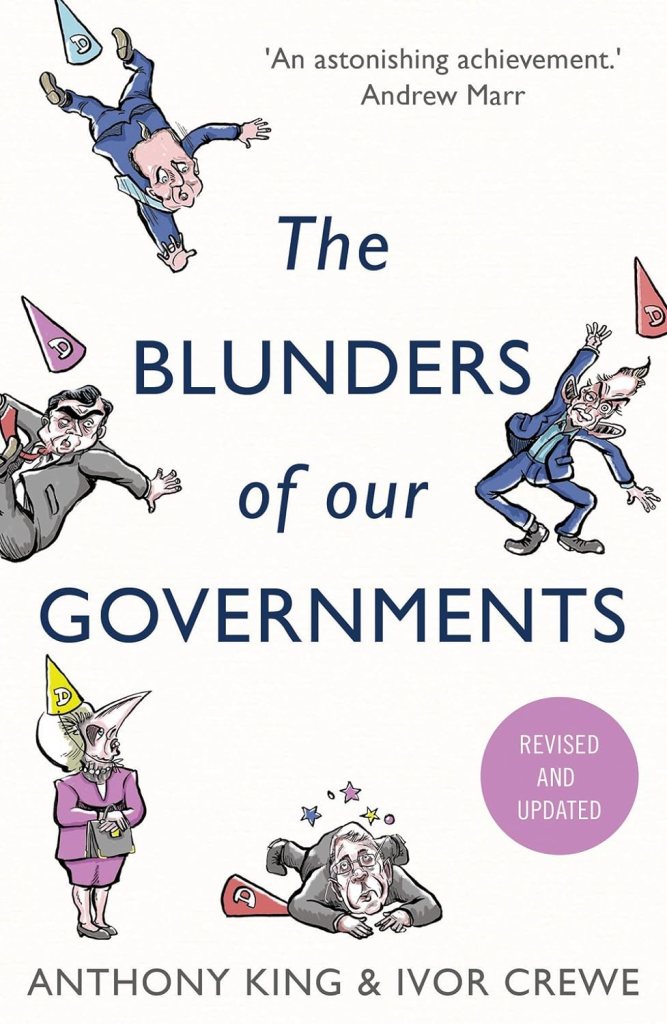

Future editions of the Blunders of our Governments will undoubtedly tackle the failure to grapple with the HE funding model over time. It is to be hoped that a new review will have the heft and the imagination to address the very real and pressing challenges faced by the sector in ways which meet the needs of all stakeholders in a balanced and sustainable fashion.

In the short term, and as I’ve argued before, in the absence of new funding and pending the outcomes of a big new shiny review, the next government needs to reduce the burden of HE regulation. Savings can be made by reducing the excessive burden of regulation on institutions and this will at least help deal with some of the current financial challenges.

Unsinking the ship

There is undoubtedly deep and widespread anxiety in the sector and people are concerned about their own jobs and futures. But universities have to keep going and have to continue to deliver excellent research, high quality education and great experiences which meet the changing needs of students while also planning for a route to a sustainable future.

Such plans – which are likely to entail change and restructuring, some of it radical – are necessary because it is likely to be quite a few years before the structural problems with sectoral funding are addressed following some form of higher ed review. In the meantime, addressing over-regulation will offer some positive encouragement to universities and mean some of that excess ballast will be ditched, ensuring the ship can stay afloat.

The prospectus of gloom needs to be binned. Telling people that the boat is going under only encourages them to head for the lifeboats. The ship really isn’t sinking. Yes there are holes but they can be patched up and the engine fixed so we can get to port for the full refit before heading out to sea again. The higher ed sector is not the Titanic.

This article represents the personal views of the author.

Leave a comment