In the red

A recent Guardian leader noted that almost a quarter of universities

are taking a scythe to budgets and planning to shed staff. The Office for Students (OFS), the university regulator established in 2017, has predicted that 72% of higher education providers in England could be in the red by 2025-26. Up to 10,000 redundancies or job losses are in prospect. The Royal College of Nursing has warned that nursing courses are being “engulfed” by the cuts, even as the care sector seeks to fill 40,000 vacancies. Arts and humanities subjects are also in the line of fire.

Responses to this on the letters page describe it as an “existential threat” to UK universities.

Leaving aside the irritation prompted by the headline that it is only academics who are paying the price for Westminster’s higher education policy failings, the leader and the letters in response do reflect the despondency and despair in large parts of higher education at the moment.

It is getting worse for sure. I’ve written a few times over the past year about the gloom enveloping the sector and noted that every day brings another story about planned cuts to courses and disciplines or redundancy programmes at one university or another. Everything seems to be looking bad pretty much everywhere and there is much talk of some universities being on the brink of insolvency.

As I’ve noted before though, despite the scything of budgets, universities still do amazing work in providing outstanding higher education to many hundreds of thousands of students and undertaking world-changing research which adds huge value to the economy and society.

Summer breeze

At the time of the last election in July 2024 I was not alone in looking forward optimistically to a slightly brighter future for the UK sector. Part of my optimism was based on the opportunity to cut burdensome regulation and the hope that there would be a reversal of the negative government tone in relation to higher education. The latter has certainly happened but we are yet to see a reduction in regulation and we are certainly a long way from HE being a funding priority. Indeed, if anything universities are dropping down the list in the face of competition from other areas of need from the NHS to European defence contributions.

Back then I was also hoping for a major review of the sector – something really chunky which would resolve all of the current contradictions and set us on course for a sustainable future. Recently Adam Thompson MP, Chair of the All-Party Parliamentary University Group, commenting to Research Professional News, expressed a wish for a “deep review” of the current system involving all stakeholders which would help lift the sector out of what he described as a “doom loop.”

To me, to you

In the meantime though the response to the current challenge sits with individual institutions which will have to review their provision as Adam Thompson comments:

Another solution he highlighted is for universities to consider specialising and reviewing all courses.

“Each university is going to have to look at the provision they’re giving [and] make difficult choices to work towards a system that’s sustainable,” he said.

As the Guardian highlights then there will be many people paying a high price for the situation the sector and institutions are in. But just saying how terrible it all is and expecting somehow, despite all the evidence to the contrary, that government has the resources and the desire to bail the sector out, will not work. Nor is using their financial reserves to support recurrent expenditure on salaries something that universities can seriously consider, despite the encouragement from one Welsh Government Minister.

Universities will also need to look at ways to be bold in terms of collaboration, as I recently noted here, and it is to be hoped that government will support this approach.

We also need measures to prevent an institutional failure which would be extremely difficult for everyone for all sorts of reasons. Disorderly collapses of institutions would be hugely challenging, messy and expensive to manage and would be a massive diversion from wider sector issues too. The consequences of any failure like this for students, employees, alumni, stakeholders, the economy and the towns in which they are anchor institutions and indeed the sector as a whole would be huge. Mergers may yet emerge as the way forward but things would I think have to get really, really bad before this became a pattern of choice in the sector.

And while all of this is going on universities will have to find ways to satisfy the government that they are serious about addressing the priorities set out by the Secretary of State, including:

- Making a stronger contribution to economic growth

- Playing a greater civic role in local communities

- Improving access and outcomes

- Raising the bar further on teaching standards

- Delivering efficiency and reform for better long-term value.

All pretty straightforward, I’m sure we will all agree. But the final point here actually requires some sector level action. It needs serious intent by government to address the regulatory burden.

Walls come tumbling down

I’ve said many times before that there needs to be a sledgehammer taken to the costly and burdensome higher ed regulatory architecture. But I have never gone quite so far as Andy Haldane writing in the FT who proposed, following the US example (in rhetoric as well as reality) in essentially smashing pretty much all regulation as a starting point:

The instincts of the new US administration are to raze the regulatory tower to the ground and only then to build back on a needs-must (or needs-Musk) basis.

By design, this scorched-earth approach delivers a system shift in culture and practice. It eliminates the deadweight costs of regulatory overshoot at the risk of undershoot.

This is in stark contrast to the UK government’s approach so far. That began with the creation of a new Regulatory Innovation Office. No one would argue with the principle of regulatory innovation. But to believe the solution to regulatory proliferation is to create a new regulatory agency is gravity-defying logic.

Late last year, Sir Keir Starmer’s government began to implore regulators to prioritise growth. But as long as these bodies have statutory mandates whose primary concern is risk, not growth, this is cheap talk.

I do agree that there is a need to get serious about the regulatory burden and that bold action is required, especially in higher education. But I do not think the sector or its staff and students would be well served by sweeping it ALL away before considering what might replace it.

Having said that, I was reminded recently (in this blog) of a piece by the very wonderful and astute Alex Usher following his visit to the Wonkhe Festival of Higher Education in 2024 in which he mused on the British propensity for over-regulation:

And NONE of it is light-touch. Brits—academic Brits, anyway—are incredibly good at problematizing everything in higher education and so their regulatory systems are designed to be resilient even in the face of some exceedingly picayune critiques. Thoroughness like this is not a bad instinct, necessarily, but when there are so exhaustingly many different types of external regulation or monitoring or evaluation, this thoroughness becomes exhausting. Institutions effectively stumble from one external evaluation to the next. And what’s really wild is the widespread acceptance in the UK that all of this is desirable, that without it, public trust in institutions would dissipate and foreign students would shun them.

So, the advice I gave them, from a Canadian perspective, was basically (not quite verbatim) “Stop. Calm the F— Down. Most of this is unnecessary”

“Canada has no REF, no TEF, no KEF. We have nothing resembling the Office for Students. External quality assurance, where it exists, is so light touch as to be basically invisible. This does not stop us from having four or five universities in the Global top 100, eight in the top 200, and twenty or so in the top 500. We may not punch much above our weight, but we at least punch at it. And with a minimum of fuss and nonsense.”

So maybe there is a middle ground between where we are now and Haldane’s regulatory scorched earth. The Usher Corridor (as it shall henceforth be known), where everything has calmed the f___ down, seems like a great regulatory route to take. in the absence of new funding and pending the outcomes of a deep review, the government does need to find ways to reduce the cost and burden of HE regulation. This will help universities deliver on those other government priorities too.

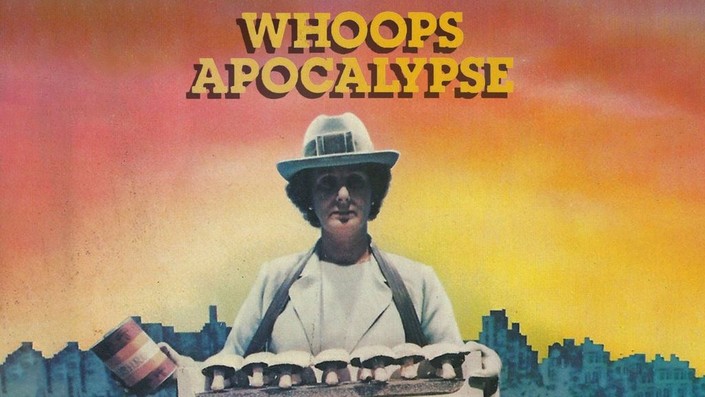

Definitely not an apocalypse

I recently looked back to see if there were any lessons which could be learned from the dramatic 1981 cuts to the sector. Despite a 15% cut to funding (15%!) all institutions survived and many thrived subsequently. If budgets are being scythed now according to the Guardian then they were being comprehensively and industrially filleted back then. And yet all of those universities – albeit operating in a much smaller and less differentiated sector in the 1980s – are still here and succeeding. Redundancies, which were at a much greater scale then than currently predicted (the Guardian’s figure of 10,000 represents around 2.5% of the UK higher education workforce), were almost all achieved through voluntary routes. It may well be different now, the numbers predicted may be an underestimate and it is not a good situation by any measure but this is still some way I think from being an existential crisis.

UK universities are packed with some of the smartest and sharpest people in the country and should be able to come up with creative ways to navigate through the current challenges towards a sustainable future. Part of the long run achievement of the University of Warwick is built on its response to the 1981 cuts. The institutional legend has it that by striking out in a different direction in the early 80s and aiming to grow when everyone else was cutting and shrinking the university set itself on the road to institutional success. That legacy and entrepreneurial ethos runs deep at Warwick (and is undoubtedly based on some historical truth) but other similar stories can be told by other institutions too. The point is that every university charts its own course and, despite the turbulence and the financial constraints, actually does have the resources, not least the intellectual capital, to do so successfully.

In the meantime all universities have to aim to keep going, continuing to deliver excellent research, high quality teaching and great learning experiences which meet the changing needs of students while also planning for this path to a sustainable future. The sector does need some assistance from government, not least in tackling the regulatory burden and preventing unhelpful intervention from the CMA where universities are looking to collaborate, but institutions still need to focus on mapping out their own destinies.

Things are tough, there is no question about that. But we really are not facing an existential crisis right now. Or an apocalypse.

Leave a comment