Vice-Chancellor Appointments and Tenure

The appointment of a new Vice-Chancellor is a defining moment in any institution’s history. Two recent reports on university Vice-Chancellor appointments offer some interesting insights into what can be a rather opaque process. The first of these, from WittKeiffer, focuses solely on the recruitment and selection process and offers some interesting observations about the approach taken by institutions. The second report, from HEPI, goes a bit further than just appointments and also covers length of tenure and the success of those who get the jobs. Both reports make a number of recommendations for change.

Things have moved on in terms of VC appointments. When I had my first involvement in supporting a VC appointment process back in 2007-08 I dug out the file from the previous process. It was from almost 20 years earlier when there were no search consultants and no options for online investigations either. The appointment committee therefore simply wrote to everyone they could think of to ask if they knew anyone who might make a good VC. The file was a collection of letters identifying a wide range of possible candidates (all of them men) and from this crude approach, remarkably it seems to me, a genuinely bold appointment was made of an individual who had a transformational impact on the university.

Risk, Reward, Priorities

The WittKeiffer piece, Risk, Reward, and the Shifting Priorities for Vice-Chancellor Selection, written by Jamie Cumming-Wesley, focuses on just 40 ‘top’ institutions in the UK and covers a decade of appointments, divided into two halves, pre- and post-pandemic (Era 1 and Era 2 in the report). In summary, the report concludes that there is a good deal of risk aversion in VC appointments, reputational issues are often involved and there is sometimes excessive caution in relation to international hires.

The key observations in relation to risk aversion are that there appears to be a reluctance to stray too far from current mission group and that prior experience as a VC is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a key factor. The author comments:

In Era 1, 44% of appointed candidates with prior experience as a VC moved from one mission group to another. This compares to just 17% in Era 2. Looking at the entire picture of appointments throughout the time periods, 40% of VC appointments involved a change of mission group for the successful appointee in Era 1, compared to just 28% in Era 2.

It is also noted that selection panels are consistently large, which can impede effective decision-making, and suggested that the split between council/external and academic/internal members can mean that the university ends up with a ‘compromise’ candidate who appeases both groups. Having supported three VC appointment panels over the years I have to say that, although the panels have all been large, this has not been my experience.

This is a fascinating finding in relation to perceived institutional reputation:

our analysis over the past decade revealed that when first-time VCs are appointed at a university within a different mission group, 100% of these appointments moved from a Russell Group institution to a non-Russell Group research-intensive university.

This does rather indicate, much as many would prefer it not to be the case, the Russell Group cachet is significant for selection panels at institutions in other mission groups. I suspect this is also about a perceived value in terms of research leadership and perhaps a feeling that the appointment says something about the institution and its ambitions.

I was particularly fascinated with the comments on international candidates:

VC longlists — although, notably, not shortlists of larger and more prominent UK institutions — contain a great deal of geographical diversity, spanning candidates from all continents.

There have been some notable international appointments in the past decade as the report notes but it is really surprising that the enthusiasm for international diversity rarely translates from longlist to shortlist.

The report suggests that selection panels may consider such candidates principally on the basis of the international ranking of their current university without giving them detailed scrutiny. It could also be speculated that it is easy to envisage more obstacles with international appointments – risk aversion coming into play again – and just feel that it all might be a great deal of trouble to shortlist someone who turns out not to be an appointable candidate.

There is a set of recommendations in the report for institutions to consider in relation to future VC appointments. Redefining selection criteria to focus on demonstrable evidence of leadership success and using competency frameworks makes absolute sense but in the cut and thrust of a selection panel and with real people under consideration these things can all too easily be set aside. Similarly, stressing the need to ensure greater diversity at longlist and shortlist stage and setting aside more time to allow full consideration of international candidates feels absolutely right but is heavily dependent on a strong chair to drive through. A further recommendation is to reduce the size of selection panels and include more external, commercial expertise. Given the number of external members from governing bodies who will be involved already this latter point does not make sense to me. Panel size is also hard to shrink in practice too. Although it might be tempting to assume that it is internal academic members who are more inclined to caution in appointments I suspect in reality it is more that those externals with limited knowledge and experience of HE who are easily swayed by reputational factors and league table positions. Although not covered here I would also add that in my experience student involvement in the process is a vital and thoroughly valuable element.

But a really interesting report which draws on plenty of real experience from an individual who knows his stuff in relation to VC searches.

Who Leads Our Universities?

The second report, from Tessa Harrison and Josh Freeman, published by HEPI, looks at the appointment and tenure of a larger group of Vice-Chancellors than the WittKeiffer paper although there will be some overlap. The report also goes on to consider VC performance, an altogether more problematic area which we will come to shortly.

Starting with the survey though, these are the key findings:

- There has been significant turnover at the top, with nearly half of vice-chancellors being appointed since 2022. Vice-chancellors have been in post for an average of four and a half years, less time than the average FTSE100 CEO.

- The vast majority (115 of 153) were already in a senior leadership position at a higher education institution before their current job, most commonly deputy vice-chancellor (72) followed by pro-vice-chancellor (24). A third of Russell Group vice-chancellors held a vice-chancellor role at a different institution first.

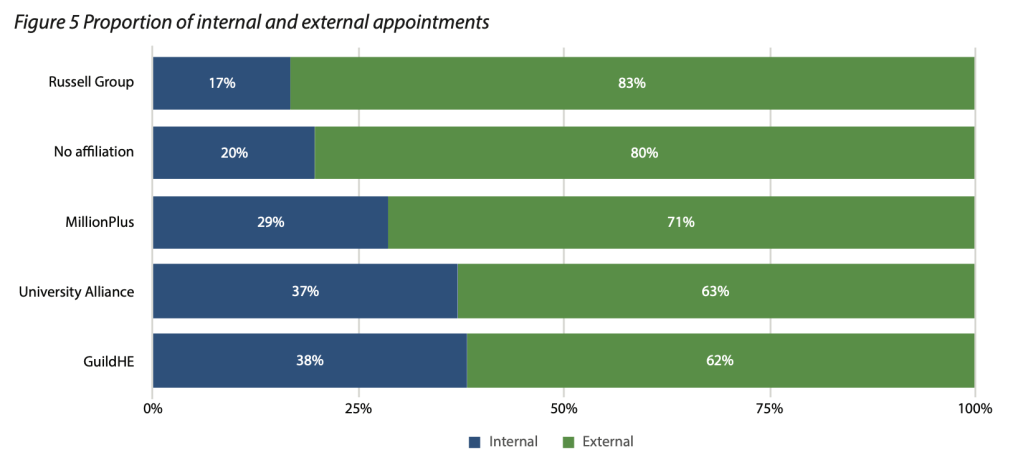

- Around a quarter of vice-chancellors (38) were recruited internally. The majority were recruited from institutions in the same mission group (MillionPlus, University Alliance, Russell Group, GuildHE).

- Around one-third of vice-chancellors (49 of 153) are women, and most female vice-chancellors were recruited in the last five years.

All of the data in the report helps to paint a clear picture of the state of university leadership in the sector and, in combination with the WittKeiffer information, we are left with a good overview of how things lie. The increasing proportion of female VCs is good to see but the average tenure does feel to me to be short (although it is an average). The proportion of internal appointments is higher than I would have expected but it may be it has always been at this level:

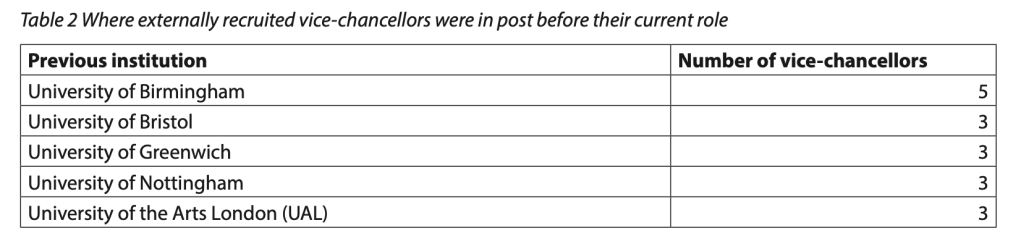

The other interesting point about external appointments is that the 92 vice-chancellors recruited externally came from 66 different UK-based institutions:

refuting the idea that vice-chancellors all come from a small number of institutions. Of these 66, 20 institutions were previously home to two or more current vice-chancellors and a small number were home to more than two. More current vice-chancellors came from the University of Birmingham (5) than any other institution.

There is plenty of other data in here too to explore so all good so far.

Measuring VC ‘Performance’

But then there is a section in the report which seeks to assess the ‘performance’ of VCs in terms of the league table position of their institutions during their tenure. The report concludes:

Vice-chancellors from outside the sector and those who previously held a vice-chancellor role elsewhere perform the best in university league tables. Vice-chancellors from the Russell Group and foreign institutions perform the worst, even when compared to those from other mission groups.

And

those who were previously deputy vice-chancellors by far the most common role for those who go on to be vice-chancellors – do not reliably secure increases in rankings for their institutions. In fact, their institutions tend to decrease slightly in rankings.

I do find this all really troubling not least because using league tables, themselves extraordinarily dubious means of assessing the relative success of institutions, as a vehicle for judging VC performance is just a really bad idea for a number of reasons:

- It assumes that VCs can exert a meaningful influence over the aspects of the rankings – these are multi-dimensional, drawing on a number of different data sources which it can be very difficult to impact, by a VC or anyone else;

- It accepts that changes to some fundamental university activities can happen rapidly whereas most of the indicators in league tables are lagged, sometimes by years and, in any case, often change only marginally over time;

- Perhaps most importantly, it signals to governing bodies that this is a reasonable way to measure the performance of their VC. If a university is defining success of its VC purely in league table terms then they are going to run into problems. And the VC’s priorities are potentially going to be significantly distorted by chasing matters over which they have very little direct control.

There are many other issues with this too, not least the fundamental flaws inherent in the rankings themselves. So I am not sure this is a sensible area of work to develop further in this way. And I really do not think we can take as a finding that VCs recruited from outside the sector are higher performers and that DVCs who are promoted internally to the VC role perform worse.

There is further discussion about the obstacles to appointing those from outside the sector and what is characterised as a cautious or ‘safety first’ approach to VC selection:

Despite these challenges, there continues to be a reluctance to consider those without an academic background. For institutions facing severe financial challenges, it may be riskier not to try a new approach. The longstanding assumption in the sector that academic credibility is the most important qualification for leadership undervalues the diverse experiences and skills that leaders from other sectors might bring and limits the sector’s ability to find new solutions to its challenges.

Whilst it may be an assumption for many there are also some solid reasons for academic leadership of academic institutions as set out for example in Amanda Goodall’s very good book Socrates in the Boardroom.

It really is not a given that a VC appointee who is external to the sector will herald the kind of new thinking and change of approach which will guarantee success in turbulent times.

In terms of recommendations the HEPI report covers similar ground to the WittKeiffer paper and makes a series of suggestions including: clarity about the VC role and requirements; the composition, training and rules governing the operation of the selection committee; focusing on the candidate experience; and supporting fully the induction of the new VC.

Defining moments

Every Vice-Chancellor appointment is a defining moment for a university. The individual selected to be the leader for the next five or more years will have a major impact on many aspects of the institution and will build on what has gone before and lay foundations for what will come after. They may also do some really special and interesting things while in office. But they do, undoubtedly, matter and this is why every aspect of the process of appointing a VC requires significant attention. Both of these reports provide some useful insights into what is generally less than transparent activity in universities and some sensible pointers (judging performance via rankings aside) to anyone involved, from those chairing or serving on selection committees to the Registrars or equivalent supporting them.

(There is a complementary piece from AHUA on the tenure and role of Registrars published last year if you are so minded.)

Leave a comment