Things can only get better, right?

I wrote a piece a while ago looking back at the HE cuts of 1981, a time when things were arguably similarly challenging to where we are now, although the sector was very different then and significantly smaller. The 1981 cuts, draconian as they seemed at the time, nevertheless did not directly lead to the closure of any institutions and those which faced the biggest losses in funding survived and indeed some have thrived since then. Things may be bad now but they are not necessarily catastrophic and it is to be hoped that it is going to be possible to navigate a way through all this which will lead to a brighter future.

Of course things are very different now in many ways from 1981 but there are some strong parallels and some important lessons to be learned, not least the need for clear-headed support arrangements, promoting real collaboration between institutions, addressing the burden of regulation and moving to a new longer-term settlement for higher education. Help will be necessary though if universities are to get out of intensive care.

Universities on the brink?

The situation is grim as a couple of details published in the notes of the Chief Executive’s report which emerged from the February meeting of the Board of the Office for Students (OfS) indicated:

We have reallocated 33 FTE towards financial sustainability and market exit activity. We have benefitted from this additional direct engagement and it is improving our oversight of financial risk at providers.

We have commissioned five professional accounting services firms, under the framework agreement, to perform deep dive financial monitoring reviews at individual providers.

And as noted in the OfS Annual report for 2024-25 and reported in the THE:

around one in six institutions on the Office for Students’ register were subjected to “formal monitoring” by the regulator over their finances last year, while five had a “student protection direction” imposed because of a “material risk of closure”.

The OfS also received an extra £1.5m from government

To provide additional capacity and a greater range of expertise to evaluate the financial risks and transformation plans of individual providers. We drew on this support when the financial context of an institution was particularly complex, including for example, where it was addressing significant strategic change or a complex business model.

In terms of the additional input from the accounting firms the report says that they can

offer targeted advice to the OfS and individual providers, prompting providers to take earlier action to improve their financial position and protect the interests of students.

Assuming this is allied to other future developments, including some form of transformation funding and a Special Administration Regime, then it is a welcome step. The re-orientation of staff to focus on these matters does represent something of a departure for the OfS whereas the regulator’s predecessor body, HEFCE, would have seen such activity as a fundamental part of its role. It is also important to remember that there are many institutions on the regulator’s books – there are around 430 in total on the Register at present – many of them new and small and lacking some of the resilience of more established universities. But as the recent extreme financial challenges at the University of Dundee show, problems can strike anywhere.

Higher Education – a risky business

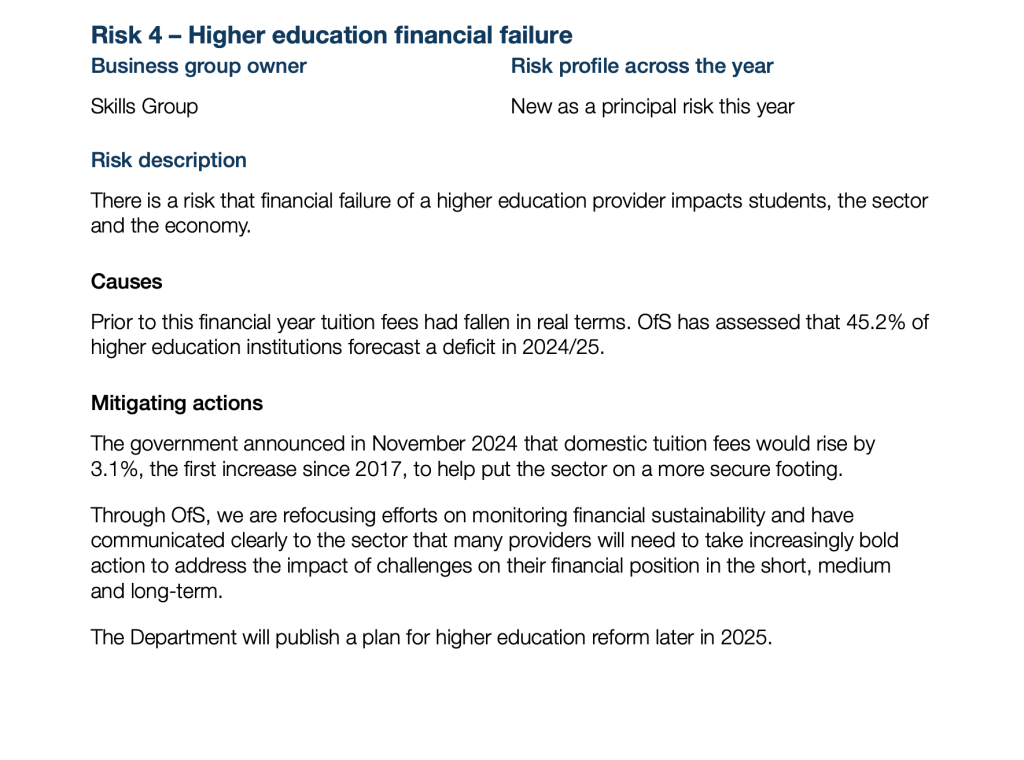

As recently noted in Research Professional, the risk of higher education financial failure is a new principal risk, escalated to the top-tier in the Department for Education’s annual report published in July which said the risk rating had been “escalated” to “critical – very likely” in 2024-25:

“The risk of higher education financial failure is a new principal risk, escalated to the top-tier this year”, the DfE said in the document. It added: “There is a risk that financial failure of a higher education provider impacts students, the sector and the economy.”

Meanwhile in its annual report, the Department of Science, Innovation and Technology stated that higher education financial sustainability was a risk that could see the closure of “significant research departments”.

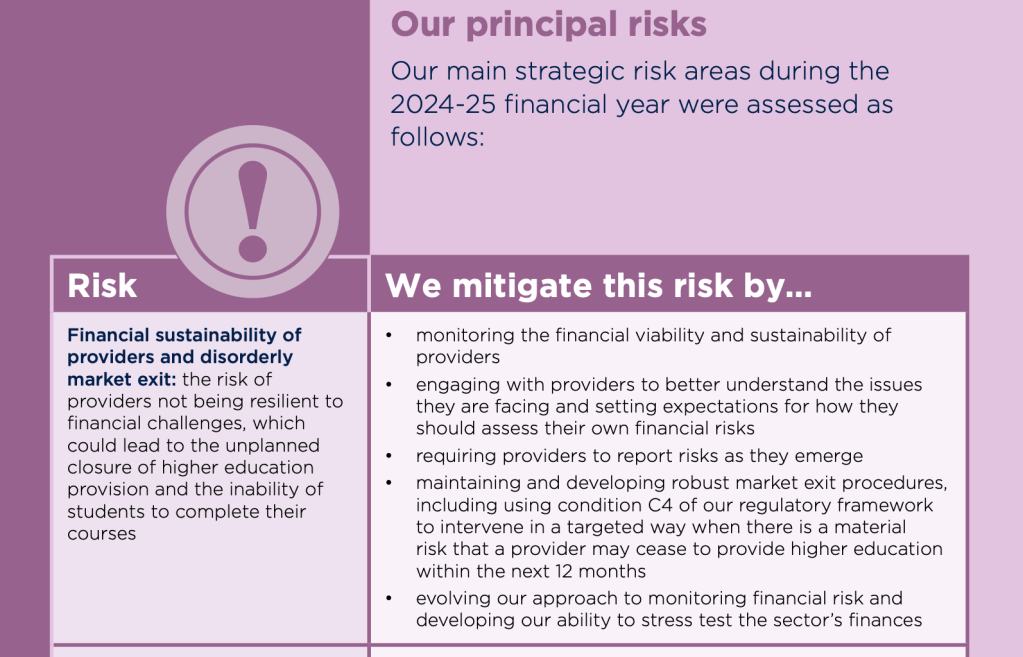

And finally the OfS itself has escalated the risk in its annual report too:

To many this will feel like belated recognition of a major set of challenges which have been known for some time. But it is encouraging in that the formalisation of these as critical risks demands that mitigations be put in place to address them. We don’t yet know what all of these mitigations are but they will be happening.

A disorderly exit would be bad for everyone

A disorderly collapse of one or more institutions would be hugely challenging, messy, time-consuming and expensive to deal with and would be a major diversion from wider sector issues too. The consequences of any failure like this for students, employees, alumni, stakeholders, the economy and the towns in which they are anchor institutions and indeed the country as a whole would be far-reaching. Having identified the risks we do therefore need some meaningful measures to be taken by the regulator and the government to prevent an institutional failure and the possible knock-on effects this would cause.

A previous blog post noted proposals made in a Public First report for the creation of a new Transformation Fund to support institutions looking to reorganise in order to reduce the likelihood of disorderly exit.

This remains a sensible and important step which would support change. A similar provision was put in place during the pandemic although the strings attached made it a very difficult offer to accept for almost every institution. Things will be different now, both in terms of the level of need and the willingness to accept a range of restrictive conditions as the price for accessing the funds needed to support major organisational change and to improve the prospects for survival.

To the lifeboats

A different piece earlier this year noted another element of the Public First report which recommended the creation of a new HE Commissioner who would have responsibility for overseeing financial sustainability and for administering the Transformation Fund mentioned above. They and their team would be based in the DfE:

To act as the primary liaison between the sector and the regulator, with a view to overseeing financial sustainability and efficient engagement in future. It would be the duty of the HE Commissioner and team to investigate instances of financial vulnerability in the sector, whether identified by the institution itself or by the regulator.

What this approach does is establish a formal model which is rather similar to that deployed in 1987 at University College Cardiff when it was facing insolvency and it ultimately led to a successful turnaround for the institution. (Full details of the events relating to UCC can be found in Shattock, M (1988) Financial Management in Universities: The lessons from university college, Cardiff. Financial Accountability & Management, 4(2), 99–112.)

In practice this would see small teams of professionals drawn from other universities and/or the ranks of recently retired senior leaders with finance and management expertise as has also recently been put in place at the University of Dundee in order to manage necessary changes and turnaround.

Public First, in the same paper from 2024 suggested that, in addition to an HE Commissioner, there should also be a Special Administration Regime to support universities on the verge of collapse. This would be the next stage in the event that the taskforce of sector experts and external specialists is unable to deliver the required turnaround.

Philippa Pickford, Director of Regulation at the OfS, was quoted on Wonkhe in relation to such a model:

OfS has now said that it is talking to government to put forward the view that there should be a special administration regime for higher education.

It is positive that the sector’s regulator is also arguing for this but it also shows how limited the OfS powers actually are. Whilst they can offer some support to institutions on the brink, in reality they are, like many, just observers of the unfolding problems.

Collaborating to survive?

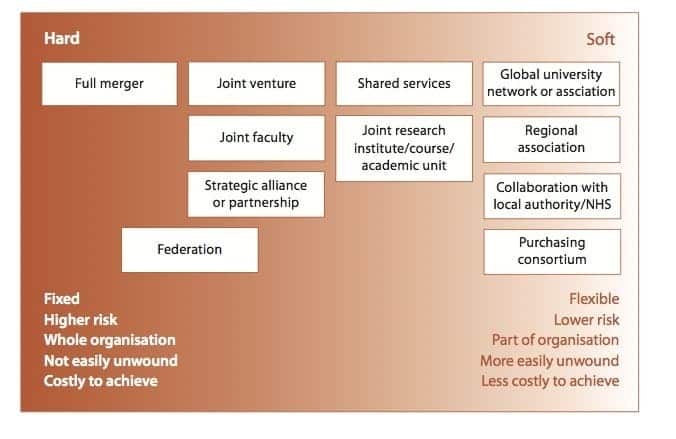

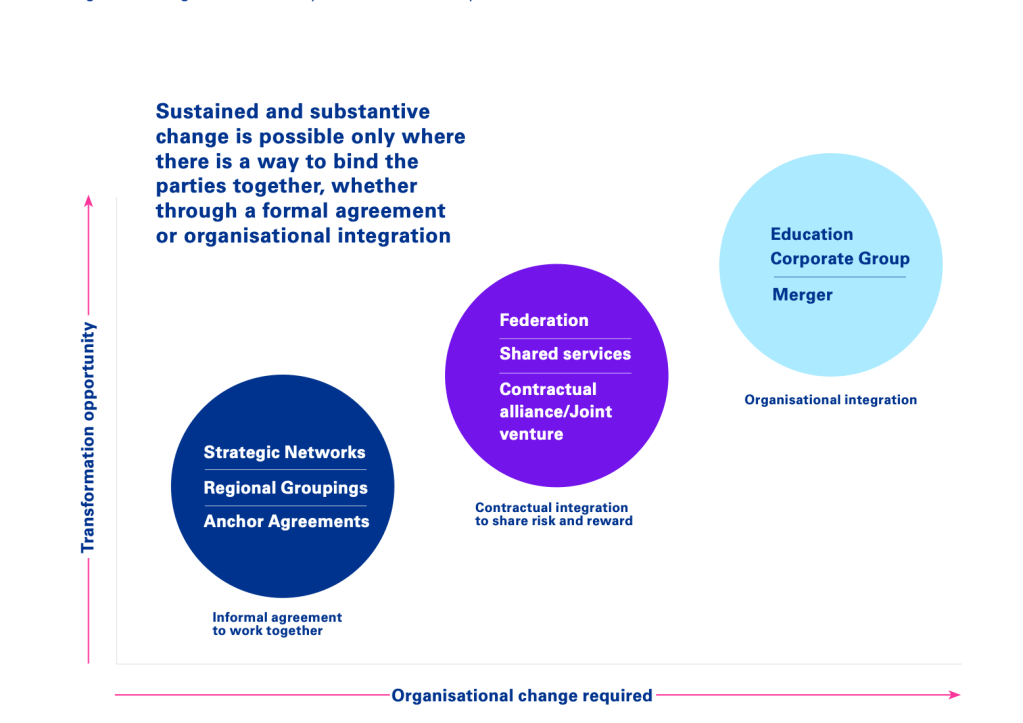

There are also plenty of ideas and suggestions about how collaborations and mergers might happen which would help address some of the challenges facing institutions. I published a piece on this recently which drew on a HEFCE document from way back in 2012 and set out some of the options. Interestingly this new report from KPMG and Mills and Reeve on ‘Radical Collaboration’ covers similar ground to the HEFCE report from 13 years ago. Both reports helpfully present the range of models available from ‘soft to ‘hard’ collaboration and the KPMG document provides some really detailed pointers for senior management teams as well as a number of case studies.

This is the summary of collaborative options in the HEFCE report:

And this is the update from KPMG:

All of the models presented, even at the softer end of the collaborative spectrum, require a lot of work, effort, time and resource to come good. Without incentives and serious financial support though, significant collaborative activity is unlikely to proceed. It may be that it will take the intervention of an HE Commissioner or the introduction of a Special Administration Regime to dictate terms on harder collaborations or mergers.

It is encouraging that the OfS is arguing for the introduction of a Special Administration Regime. I do think this does have to happen sooner rather than later. We can’t wait until the reforms promised in the post-16 white paper later this summer. By then it might be too late for some. And if this all sounds difficult and expensive it is as nothing compared to the cost of a major public university going under. The massive efforts which would be required to address all aspects of winding up a university are staggering to contemplate

Not bankrupt but in need of support

Everyone is all too keenly aware that universities are facing major challenges. There are no easy ways out as the very public increase in risk levels and the need for transformation funds, commissioners and a Special Administration Regime demonstrate. In this context it was perhaps surprising to see a bit of an uneven article in the Economist recently, latching on to a think-tank report from 2021.

The Economist seems to have a quite distinct angle on HE issues, suggesting that universities have had far too much money and squandered much of it. Somehow it is their own fault they are so expensive and they need, apparently, to be incentivised to be more efficient.

Leaving aside the historical structural reasons for the model we currently have and the failure of governments to address the broken funding structure which exists, some of the fundamental issues include the decline in the value of the home student fee, the lack of any capital funding, growing expectations of services and facilities for students, the chronic under-funding of research, the excessive burden of regulation plus, critically, the dependence on the hugely volatile business of recruiting international students to compensate for all the other funding shortfalls.

The article suggests universities have “binged on grand campuses” but with no capital provided there was a need for institutions to address historical under-investment in their estates and the only choices they had were to use their own resources or borrow. Given the highly competitive environment they were now expected to operate in they also had to address campus offerings and attractiveness to potential students. A new learning resources centre or shiny sports facilities are inevitably going to look like more positive options for the prospectus than presenting investment in backlog maintenance or repairing a district heating scheme.

Similarly, in order to compete internationally for both staff and students, universities have to invest in research and researchers. Funding arrangements simply do not support the need though and it seems that government continues to expect a Lexus standard of research output for the price of a Honda Jazz. Continued expansion of international student numbers is the driver for all university finances at present and when that slows there is a problem for everyone. All of this is presented somehow as being the fault of profligate institutions and students who insist on studying away from home. Part of the solution for the Economist is offered in the form of a 2021 report from a short-lived think-tank, edsk, which proposed:

splitting universities into “national” and “local” institutions. National ones, such as Oxford and Cambridge, would be tasked with climbing league tables and attracting the brightest minds. Local outfits would offer the best possible training at the best possible cost. Such thinking remains radical in Britain, but is quotidian elsewhere.

Those local universities would be limited in the range of their activities, have a low cap on the number of international students they could recruit and be overseen by a new Tertiary Education Commissioner.

In a later report the authors went much further in developing a state-directed but devolved higher education model. Unfortunately, this model, which requires Combined Authorities to adopt the principal oversight role (but still with some central regulation), fails to recognise the nature of the HE ecosystem and really feels more like a nostalgic journey to the days of a large public sector for HE, a national planning body (NAB), polytechnics and local authority control, all of which was swept away in the major changes of 1988 and 1992. The desire for joined up arrangements across the tertiary landscape is understandable but the wish for this to happen under the auspices of combined authorities seems a step too far. We really need something different both to this kind of statist model and the more laissez faire arena developed following the Higher Education and Research Act 2017.

It’s a pretty poor ragbag of an article although it is, rightly, critical of university rankings and the negative impacts they can have on university behaviours. Whilst there is undoubtedly scope for universities to address inefficiencies – and all are doing that right now – it fails to address the constraint and cost of excessive regulation which will only grow under the model presented.

And finally…reducing regulation and a new review on the road to recovery

I’ve written many times about the excessive burden of regulation on higher education and set out proposals for addressing it, including most recently this piece on ideas for a new regulatory framework and this blog which presents some suggestions for regulatory changes which could lead to savings of £500m a year for the English sector. The burden of regulation does have to be addressed as part of the package of measures needed to deal with the challenges higher education right now.

In addition then to these immediate steps, we do need a serious longer-term review of the whole higher education model. It is broken and has to be fixed. Transformation funds, HE commissioners, a Special Administration Regime and tackling the excessive cost and weight of regulation can all be progressed right now. Things are bad now but not catastrophic. Yet. These immediate actions need to be taken by the regulator and government to enable institutions to help themselves.

A proper, heavyweight and far-reaching HE review will take time and, while some reforms to the higher education model are expected – in its annual report the DfE said it “will publish a plan for higher education reform later in 2025” – we really need this to be detailed, comprehensive and bold. In the meantime, there is plenty to be getting on with to ensure that universities can get out of intensive care and start on the road to recovery.

Leave a comment