He never really went away

With the huge challenges currently facing the higher education sector in the UK, many institutions are, unsurprisingly, reassessing their course portfolios. There is logic to this, as if it is very hard to recruit students who want to study a particular degree course, either because the competition with others is so fierce or the subject is just wildly unpopular, then it does not look sensible to continue to offer it given all of the costs. But it isn’t that simple of course. The degree course in question may be just one of a few offered of this type and if they all go then that subject is lost for good – it is really hard to start something again from scratch once it has been wound up. Also, the subject may be one which it is in the national economic interest to sustain. Just because students aren’t choosing it does not mean it should be closed down as it may do longer term economic damage to do so. And then there are all the students who choose other courses who need a bit of this one, maybe just one or two modules, as elements of their degree programmes. And all of that is before we get on to the broader impact on all of the staff involved, many of whom may be leading researchers in the discipline and the institution may be reluctant to lose for other reasons. Mergers of departments and realignments of subjects is one approach to dealing with all of this but if, at the end of the day, an institution has the same number of courses and staff and declining student numbers then that probably does not represent a great way forward.

It started with a speech

Institutions, their leaders and staff, have been grappling with all of this for a while now and will be continuing to do so no doubt for some time to come. But the media really are much more interested in rather different angles on course provision. Any course which appears in any way non-traditional can be selected for abuse as being from the ‘Mickey Mouse’ stable – regardless of the career successes of its graduates (pretty much any course not offered at Oxford or Cambridge before the millennium). This piece in Research Professional from a few years back offers a brief history of the Mickey Mouse Degree and attributes the origin of the term to a speech by a former Labour Minister Margaret Hodge (now chair of a University governing body) when she first coined the term “Mickey Mouse degrees”:

Back in 2003 at an Institute for Public Policy Research event, she defined a Mickey Mouse degree as “one where the content is perhaps not as rigorous as one would expect and where the degree itself may not have huge relevance in the labour market”.

She also told vice-chancellors that “simply stacking up numbers on Mickey Mouse courses is not acceptable”. Roderick Floud, president of Universities UK at the time, condemned the minister’s language and challenged her to identify specific courses that merited the name. Phil Willis, Liberal Democrat education spokesperson of the day, called Hodge an “out-of-depth minister” in a “Mickey Mouse government”.

And this was from an administration that wanted to increase the number of students going to university.

Despite the obvious libel on the Disney corporation, the term “Mickey Mouse degrees” stuck, notably because of its frequent use in the tabloid press. But not everyone was against these courses—and just like now, no one minister would dare name them.

Some newspapers, unlike ministers, do seem quite keen to identify some programmes they see as Mickey Mouse degrees. Part of the critique here is that these degrees are somehow not legitimate because they are too specific or vocational and that they don’t enable graduates to earn decent salaries. Leaving aside the contradictions in a stance which is both anti-vocational and pro-well-paid-job what this kind of article demonstrates is underlying hostility toward the universities which offer these courses (given the transparency requirements around courses these days can they really be said to be deceiving students with their offers) and the students who choose to enrol who seem somehow not to be worthy of being students. There really is a huge amount of snobbery and ‘more means worse’ sentiment here.

Show me the prospectus Harry

Over the years I’ve looked occasionally at the kind of distinctive or niche courses on offer across the wonderful world of higher education (including this reminder of offerings featuring musicians, principally Beyonce and Taylor Swift, and the paranormal) so thought it was probably time to highlight a few recent examples.

Wikipedia, which also attributes the term to Margaret Hodge, offers a few more early examples including a module on football culture offered by Staffordshire University which featured David Beckham and a module run by Durham University (some years ago now) as part of an Education degree on ‘Harry Potter and the Age of Illusion.’

Texas State University hit the headlines with its module on “Harry Styles and the Cult of Celebrity: Identity, the Internet, and European Pop Culture.” The class was intended to focus on

Styles and popular European culture to “understand the cultural and political development of the modern celebrity as related to questions of gender and sexuality, race, class, nation and globalism, media, fashion, fan culture, internet culture and consumerism.

Exeter University managed to generate lots of media excitement about its module, offered as part of a Communications, Drama and Film programme, which explores how donkeys have been represented – or misrepresented – and treated in movies including The Banshees of Inisherin, Shrek and EO (which had a rare starring role for a donkey):

Students and staff from the university, which has campuses in Devon and Cornwall, will work with staff at The Donkey Sanctuary in Sidmouth, Devon, observing and recording their interactions with the animals.

Dr Faith Burden, Deputy CEO of The Donkey Sanctuary, said: “For too long donkeys have been misrepresented in popular culture and this has done them a great disservice.”

There is a big hitting doctorate over at Centenary University where you can shape the future of well-being with the world’s first PhD in Happiness Studies.

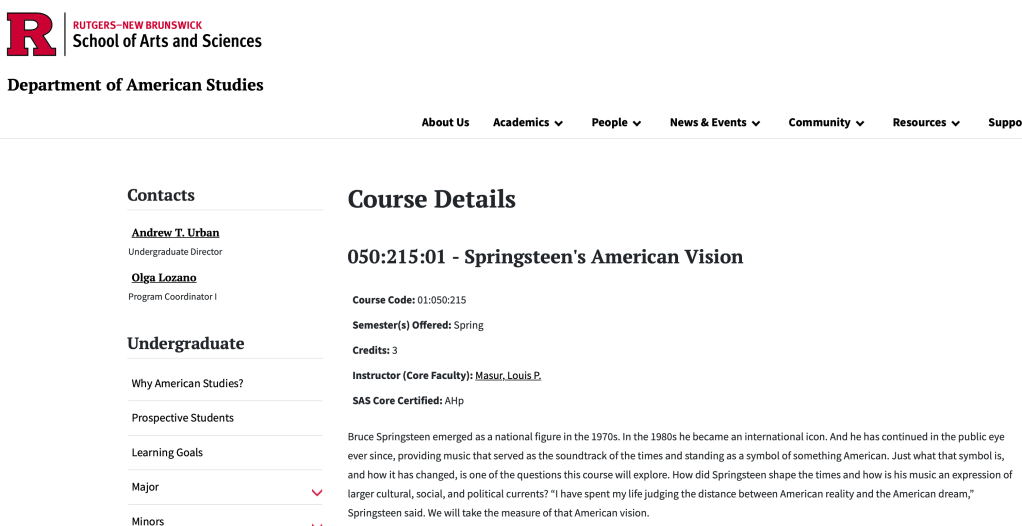

This one has run and run, almost as long as the artist himself. In a Chronicle podcast you can hear a discussion about a long-standing module at Rutger’s University on ’Springsteen’s American Vision’:

For decades, Bruce Springsteen’s songs about fast cars, working-class dreamers, and loves lost and found have helped to define a quintessentially American notion of freedom and rebellion. But do the music and lyrics of “The Boss” speak to the college students of Gen Z? Louis P. Masur, a distinguished professor of American studies and history at Rutgers University, thinks they do. After years of teaching a course titled “Springsteen’s American Vision,” Masur says he is as convinced as ever that the rock legend’s songs are as timeless as Huck Finn and as durable as a “big old Buick.”

There is much more of this kind of thing out there.

There will be more

As all of this shows, beyond whole degrees, however defined, any course or module which features any kind of analysis of a popular star, especially a musician, seems to be fair game for critique. More recently though with the advent of free speech arguments there has also been a focus on trigger warnings and fears of ‘decolonisation’. We will perhaps look at some of them another time. Until then though, what is your favourite niche but absolutely non-Mickey Mouse course offering?

[“Mickey Mouse.” by skyseeker is licensed under CC BY 2.0.]

Leave a comment