Is everyone in it for the right reasons?

Transnational Education (TNE) has long been an area in which UK universities have been pioneers. The latest report from Universities UK (UUK) on TNE activities demonstrates how much such operations have grown in recent years. According to UUK the numbers have increased to involve over 650,000 students, a 70% increase in the last decade.

Some highlights from the summary report (the full one is yet to be published), titled The scale of UK higher education transnational education, include the following:

- 653,570 students were studying UK higher education overseas in 2023–24, across 173 providers in 231 countries and territories.

- In-person UK HE TNE provision is growing fastest, with 491,765 TNE students studying in person in 2023–24 – an +87.4% increase over the past decade, compared with +32.5% growth in distance TNE over the same period.

- Global demand for UK TNE is rising: UK HE TNE student numbers in Saudi Arabia grew by +142.2% in five years, Sri Lanka by +104.2%, and the United Arab Emirates by +88.1%. Beyond the top 10 hosts of UK TNE, several nations are rising rapidly: in five years, Vietnam has grown by +233.9%; Nepal by +107.5%; Pakistan by +103.0%; and India by +78.1%.

- The most significant growth in five years per type of TNE provision has been in students registered at an overseas partner organisation (+72.5% increase), and in students studying via collaborative provision (+58.0% increase).

Beyond this there have been some big headlines about UK and other universities looking to establish physical presences overseas.

All Around the World

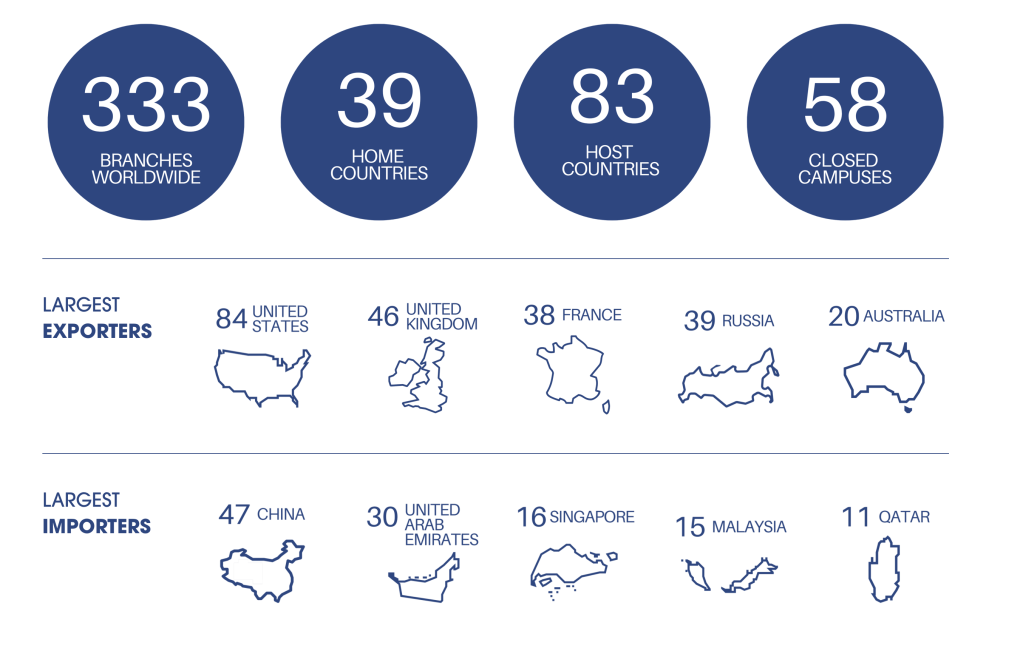

C-BERT, an outfit which produces regular reports on branch campus developments, has shown the latest set of branch campus developments to be as follows:

That’s a lot of campuses and the numbers continue to grow. As the following examples show.

In October 2025 there was big news about new branch campuses to be opened by UK universities in India:

United Kingdom Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer has confirmed that Lancaster University and the University of Surrey have been given approval to open new campuses in India as part of a planned major expansion of UK universities in that country.

The UK government believes the two new campuses announced on 9 October during Sir Keir Starmer’s two-day trade mission to India have put the UK on course to be the country with the “biggest higher education footprint in India”.

The UK’s network of international campuses in India is growing – the University of Southampton opened a campus in Delhi earlier this year. The University of York, University of Aberdeen, University of Bristol, University of Liverpool, Queen’s University Belfast, and Coventry University will open campuses from as early as next year.

To be fair this news has been expected for over 20 years now but good that things finally seem to be taking off in India.

The THE also reports that, following the well-established activities of Nottingham and Liverpool, Exeter is getting in on the action with a joint institute in China:

The University of Exeter plans to open a joint institute in China catering for up to 1,200 students – the institution’s first major overseas campus.

The institution said it has received approval from China’s Ministry of Education to create a “world-class education institute” in partnership with Zhejiang University of Technology (ZJUT).

Commencing September 2026, students will graduate with a dual degree from both institutions.

The new institute will be based in Hangzhou, the capital city of China’s Zhejiang province.

Meanwhile the University of West London is expanding operations in Sri Lanka with plans to open a branch campus. It aims to establish a new base in Colombo, partnering with a private HE provider:

UWL has been running degree programmes in the country since 2013, with almost 5,000 students graduating in subjects including business, law, psychology and computing.

The formal redesignation of the partnership as a branch campus will give students direct access to UWL’s academic standards, degree pathways and student representation, as well as access to a dedicated, visibly branded site.

Peter John, vice-chancellor and president of UWL, said the development was an “important step” in the university’s global ambitions. UWL’s launch follows similar moves by Australian universities expanding in the region.

Last year, Curtin University opened a “fully fledged” Sri Lanka campus at the Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology in Colombo, transforming a two-decade teaching partnership into a full campus with programmes in artificial intelligence, health and the humanities.

THE also reports that Vietnam is keen for “at least two more branch campuses to launch this decade” after reforming its regulations and aiming to become an international hub. THE notes in relation to UK interest that Southampton is keen:

There is currently only one international branch campus in Vietnam, Australian-owned RMIT Vietnam. Other universities have opened with foreign investment, including the British University Vietnam (BUV) and the Vietnamese German University in 2008.

Andrew Atherton, vice-president international and engagement at the University of Southampton, said Vietnam was now one of nine global priority countries for his institution because of “a confluence of significant economic development and growth, and a regulator that is open-minded and enabling but clear in terms of the regulations”.

The THE also recently noted that more universities were hoping to be the first to establish themselves in Saudi Arabia, despite some of the significant reputational challenges associated with operating there:

The University of New Haven from the US and Scotland’s Heriot-Watt University are the latest to have announced plans to open campuses in the Gulf country, eyeing the next transnational education hotspot after numerous Western universities launched in nearby United Arab Emirates. They join Australia’s University of Wollongong (UOW), which became the first foreign university granted an investment licence in April.

Nigel Healey, who knows a thing or two about TNE, is quoted in the piece:

“Strong economic growth, a political strategy aimed at liberalisation and diversification enshrined in Vision 2030, and favourable demographics are strong pull factors, which are already tempting the first wave of Western branch campuses from foreign universities with a long track record in the region.”

But unlike the UAE, Healey said the oil-rich country, where homosexuality is illegal and carries the death penalty, remains deeply conservative and autocratic under Muhammad Bin Salman.

“This rigid social and religious environment, combined with a poor record on human rights, is anathema to the values of many Western universities,” he added.

It hasn’t stopped footballers and comedians.

Also controversial is Cardiff’s establishment of a branch in Kazakhstan as noted in this more than slightly hostile news report:

Fresh concerns have been raised about Cardiff University’s recently opened branch campus in Kazakhstan after details of its registration with the Kazakh equivalent of Companies House were published.

The decision of the university to set up an offshoot campus in Kazakhstan has been controversial, especially at a time when it has been imposing drastic cuts, including many job losses and school closures, on its home operation in Wales.

Closer to home some international branch campuses will soon be set up in Greece following a change in the law. Three UK universities – Keele, York and the Open University – are in the first tranche. The University of Nicosia is also joining in the fun apparently.

But the biggest branch campus news in recent months, arguably for years, is this announcement from Australia’s Monash University about its plans for expansion in Malaysia:

Australia-based Monash University has revealed plans to open a 22,500-student campus in the heart of the Malayisan capital of Kuala Lumpur. Monash University Malaysia will partner with TRX City to deliver its 2.8 billion ringgit (AUS$1 billion) local investment into a future Monash campus.

The campus was officially announced by Monash Vice-Chancellor and President Professor Sharon Pickering alongside Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Dr Zambry Abd Kadir, Minister of Higher Education in Malaysia, and the university is working with both governments on the projects.

The campus is planned to open in 2032 and eventually scale to a capacity of 22,500 students and 1,700 staff, Monash University said.

That is huge and significantly larger than any other branch campus development. Monash is already one of the biggest branch campus operators and this will put them way beyond everyone else.

Things aren’t progressing so well in other countries though. Pakistan’s ambitions, as reported in THE, seem to have had a tricky start:

Earlier this month the regional government in the Punjab named four UK universities it claimed were in the process of establishing a presence in the area as it seeks to follow neighbouring India in becoming a hub for transnational education.

Asked by Times Higher Education about the plans, the institutions – the universities of London, Gloucestershire and Leicester as well as Brunel, University of London – all denied the reports.

Imperial College London has also since been forced to rebut claims it is set to open in Pakistan after the government appeared to erroneously announce that it would.

Uh oh.

Beyond the bottom line

From a UK HE perspective then this big growth in TNE is all encouraging to see and perhaps not difficult to predict as UK universities look to find different ways to expand their activities at a time of financial challenge. Given the generally more lucrative nature of international student recruitment it is therefore no surprise that institutions are going down this road. These are uncertain times in a world of rapid political change making such activities potentially precarious. But if it is principally about money this really is even more of a concern.

There are many ways for UK universities to respond to the need to retain their international outlook (and international student numbers) in what remains an extraordinarily challenging environment. The branch campus option is one of these, although I do think the easy way in which they are often discussed usually fails to take account of the extraordinary efforts required to establish a whole campus in another country. There is also the need to look beyond income generation as a motive.

A genuinely internationalised university brings huge benefits for its home country as well as those in which it operates. It is essential to be clear about motivations and objectives though. While some governments may see both economic and soft power benefits from exporting HE and others may welcome incoming universities’ contributions to growth and capacity building, the impact of universities’ international activities is complex and multi-faceted, and the practicalities of delivery are hugely challenging.

It really is very hard work and establishing an overseas campus is not at all straightforward. Challenges range from building the infrastructure to restructuring institutional and local governance. Legal issues, financial arrangements and developing local management can take time and significant effort, as can coming to terms with an entirely new academic, political and cultural framework. It also necessitates close relationships based on trust and taking a long-term view with partners. While it is inevitable that there will be a need to repatriate some funds to cover part of the costs of operations, it would fundamentally undermine confidence in the enterprise and credibility if it appeared that the aim was to extract money. This would simply not be sustainable in the long run.

And it is important to remember that the local political and economic environment can change pretty quickly for international campuses, particularly if the leader of one of the global superpowers suddenly takes an interest (or decides to impose new trade tariffs).

To leverage the full benefit of an international campus a university must have a strategy that goes beyond thinking about cash-generation. The management input required is high, and there are inevitably opportunity costs back in the UK. The investment is substantial, but it is worth it for a university committed to an international vision that goes beyond generating income from overseas student fees. Such a global footprint, therefore, has real impact on the institution, its students, staff and stakeholders as well as for the governments and society at home and in the countries with which it is deeply engaged.

Achieving a real and comprehensive international impact is therefore about much more than just the money. I am hoping this is the perspective all of those universities which have announced their branch campus plans recently have adopted. A quick in and out should not be something any institution contemplates in terms of branch campus activity.

Leave a comment