Will we see an end to the class war?

As regular as the debate about whether Die Hard is really a Christmas movie or not, the annual hand-wringing about “Too many firsts and upper seconds” is higher education’s hardy perennial. The growth in the award of good degrees by universities, often viewed as grade inflation, is in the news again.

It is unarguably the case that with only four main categories – I, IIi, IIii and III – degree classifications are not particularly nuanced (another Die Hard comparison perhaps). And if more and more students receive first or upper second class degrees the less useful classification is for employers looking to distinguish between candidates.

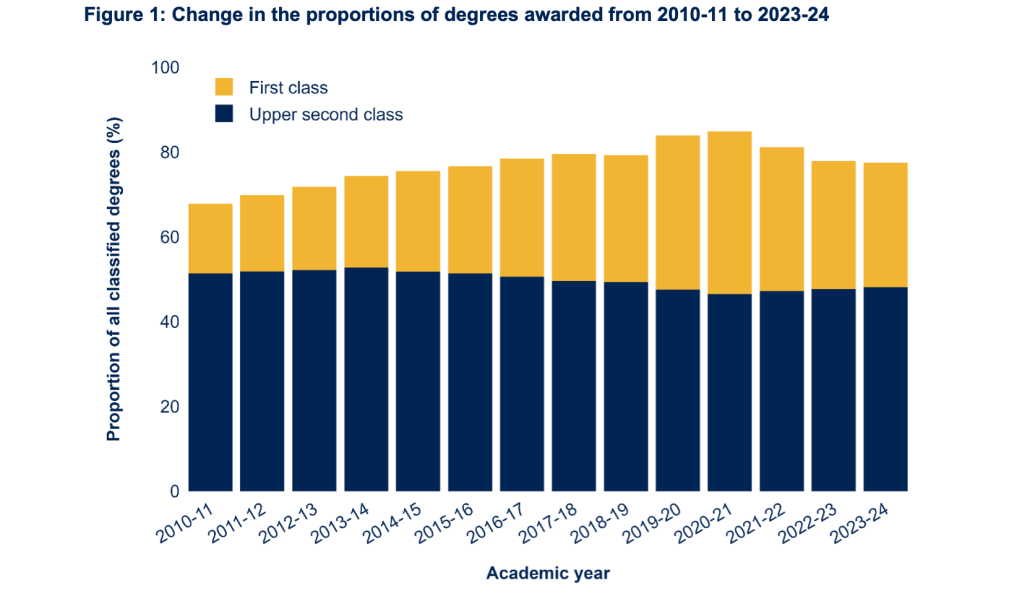

The Office for Students (OfS) has recently got excited again about degree classifications. Although the trend in the proportion of first and upper second class degrees has fallen in the past couple of years there is still a big difference from where we were in 2010-11.

One specific area the OfS decided to investigate recently was degree classification algorithms – the means by which final awards are arrived at from all of the marks achieved by students in the parts of their programmes which contribute.

There are issues here but they aren’t the one the regulator has identified. For me, this points to a need to reconsider whether the traditional UK undergraduate degree classification system, where over three quarters of students achieve one of two results, is fit for purpose any more.

Algorithm is a dancer

Let’s look first at the trends then. The OfS has jelpfully summarised this in a recent publication on degree classifications which notes:

Between 2021-22 and 2023-24 the percentage of UK-domiciled, full-time first degree graduates attaining a first-class or upper second class degree fell. In 2023-24, 77.2 per cent received a first or upper second class degree, compared with 77.6 per cent in 2022-23. This sector-wide decrease of 0.4 percentage points is the third successive year that rates have fallen, having increased considerably between 2010-11 and 2020-21.

It goes on to note that there is still an increase of 9.7 percentage points in the proportion of first and upper second class degrees awarded between 2010-11 and 2023-24.

So, over a longer period of time, the proportions of firsts and upper second class degrees has increased. The following graph shows the picture clearly:

The OfS has done quite a bit of modelling on all of this and concluded that a lot of this is down to factors which are yet to be explained:

Our model leaves open a range of causes for the observed increase, including improvements in actual student achievement over time by students with similar characteristics. However, the observed increase may also reflect other factors that might cause inflation, such as changes to algorithms or to assessment practices not aligned with changes in student achievement.

Why the anxiety? Not unreasonably, grade inflation is a concern. The idea that first and upper second class degrees are easier to obtain now than 15 years ago is not helpful in terms of reassuring everyone about the standard of those awards.

Slave to the Algorithm

As noted in its report on algorithms the Ofs has a condition of registration relating to this:

15. Condition B4 came into effect on 1 May 2022. Two of its requirements are relevant to the credibility of awards:

• To be compliant with B4.2.c the provider must ensure that its ‘academic regulations are designed to ensure that relevant awards are credible’.

• To be compliant with B4.2.e the provider must ensure that relevant awards granted to students are credible at the point of being granted and when compared with those granted previously.

The report draws on three specific investigations undertaken by the regulator at three different institutions. These enquiries represent an unprecedented dive into the detail of assessment processes at autonomous degree-awarding institutions. The regulator is principally concerned with two step algorithms – where marks derived from algorithms are considered, the lowest mark dropped and then another algorithm applied. All three of the institutions investigated included a step to discount the lowest mark, an approach the regulator views as inherently inflationary, and therefore the OfS concluded that there was an increased risk of a future breach of condition B4.

So, some strong warnings for the future then. There are also some general observations the OfS is keen to share and the report indicates the regulator’s enthusiasm for continuing to work with the sector on algorithm issues. As they put it so gently: “we expect providers to take notice.”

In summary, they don’t like extra steps in algorithms or discounting the poorest mark and are going to go in hard where institutions choose to follow this practice:

Any provider that intends to continue to include either of these steps in its algorithm from September 2026 is asked to let us know this by 31 July 2026, so we can understand the scale of continuing use of these steps. We may issue further guidance about the use of these steps in due course.

And that’s not all:

We are also introducing two new reporting requirements so we can monitor sector practice, and follow up as required with individual providers: one is to let us know where a provider is making changes that will increase the proportion of first or upper second class degrees awarded, and the other is to let us know if a provider is introducing steps either to award a student the best result from multiple algorithms, or to discount credit with the lowest marks into an algorithm.

This feels to me like a really deep intervention into the heart of the assessment process. Assessment is understood and owned by the academics who design and undertake it. The rules and algorithms are developed collectively by academics over time and adjusted in the light of experience and the sharing of practice across institutions, disciplinary communities and professional bodies. In general, decisions about changes to assessment and classification methodologies are taken carefully and systematically after due consideration. Every degree-awarding institution is, of course, conscious of the need to maintain and protect the standard of awards issued in its name and will take the steps needed to ensure this happens. This will also result in compliance with condition B4. But for the OfS to dictate parts of the assessment process feels like a significant challenge to institutional autonomy.

Algorithm is going to get you

I’ve written about this issue a number of times before including this from a few years back on the idea of moving to GPA. More recently on Wonkhe David Kernohan has explored the OfS reports in more detail and highlighted some additional points and this long article by Jim Dickinson has set out many of the issues around algorithms.

For me all this demonstrates that the current classification system is well past its sell-by date. Over a decade ago a number of universities explored introducing GPA as an alternative to traditional degree classification in order to tackle this problem. GPA, it was argued, would be:

- More transparent and better able to reflect different levels of attainment,

- Globally understood, and

- Reflective of and compatible with the culture and norms of marking in UK higher education.

Good progress was made in terms of agreeing the principles, GPA scale and marks conversion but then things didn’t take off as there was not a large enough group of universities willing to take the leap.

The Higher Education Academy (HEA), which has since become AdvanceHE, took on this work and explored how a grade point average system could operate in the UK. Ultimately though this ran into the sand as well.

The Quality Assurance Agency has also explored various means of dealing with degree classification challenges in a literature review undertaken and shared with members in 2022. It set out some of the background to developments which had taken place in the previous years as GPA was investigated by a group of universities and subsequently by the HEA.

So, why hasn’t it happened? We have the model, we have a some strong support from some institutions and there is undoubtedly a problem to be solved. Those institutions which talked about going it alone appear to have shelved the idea despite the advantages. This is unfortunate.

So where do we go from here? The arguments for GPA in the context of what looks like an ever more outdated degree classification system remain very powerful. And given the ever-growing interest of the OfS it is time for the sector to regain control and to look again seriously at GPA.

Algorithm of the night

If there is no change the sector is going to be arguing with the regulator and the media about this every year. All of this risks undermining public confidence in academic standards and the inevitability of increased intervention by the regulator also challenges institutional autonomy.

A collective decision to move to GPA would be beneficial for a number of reasons not least that it closes off this avenue for regulatory over-reach into the decision-making heart of autonomous degree-awarding institutions. But it also creates an opportunity for a period of sector-wide focus on something in higher education that really, really matters – how we best assess and recognise the achievements of undergraduates. A concerted effort to re-calibrate and reset is ultimately going to be beneficial for everyone.

Whilst there are arguments against, we nearly got there a few years ago. And there would be real benefits for all for putting this one to bed for a couple of decades at least.

Leave a comment