It does feel like the higher education sector is currently facing its biggest challenge for generations. Looking back to the major cuts to university funding imposed in 1981 though there are some interesting parallels and lessons to be learned. The sector was very different then and significantly smaller. But in many ways it seems that HE now is no not much better prepared than it was back then. The 1981 cuts, draconian as they seemed at the time, nevertheless did not directly lead to the closure of any institutions and those which faced the biggest losses in funding did survive and indeed some have thrived since then. So there are possibly some lessons that can be learned. Things may be bad but they are not necessarily catastrophic and it should be feasible to navigate a way through all this which will lead to a brighter future.

1981 v 2025

There can’t be many people working in higher education now who can recall the impact of the cuts of 1981 on the sector. Those funding reductions, imposed by the newish Conservative government and implemented by the sector funding agency, the University Grants Committee (UGC), were felt by those around at the time to be genuinely seismic.

There are some strong parallels with where the sector is now as well as some significant differences. In both cases there was a general lack of preparedness, some institutions had avoided or delayed taking difficult decisions and others were simply hoping it would all go away.

The higher education sector now though is vastly larger, both in numbers of institutions and students, there is no central planning agency – the principal regulator in England, the Office for Students (OfS) has a very different remit and, while the national funding bodies Scotland and Wales share some characteristics with the UGC, there is no sector wide body concerned with the future of higher education.

At that time universities received the vast majority of their income directly from the UGC. International student fees were subsidised, although that ended in 1980, despite campaigns against the change. Since then of course international student fees have grown to be a core part of institutional income and seen as the principal financial lifeline in some cases.

Over time higher education has become much more of a competitive environment and this was cemented in England at least by the 2017 Higher Education and Research Act (HERA) which explicitly sought to attract new entrants to the sector, drive competition between institutions, accept that market exit was possible for some and established the new regulator, the OfS, with new powers.

Many institutions have reported financial deficits for the 2023-24 financial year and others are predicting similar in future years. Some of these may be bigger than others and the savings responses, including redundancy proposals, which have been developed vary across the sector. Back in 1981, the UGC applied its cuts differentially with some universities being much harder hit than others – Salford for example faced a 44% cut in its funding whereas York only lost 6%. Looking at the way these cuts came about and were implemented and the long run impact both provides some lessons as well as grounds for optimism for the future.

The impact of the cuts did entail significant changes but everyone responded and, whilst there were certainly some universities which might be regarded as distressed no institutions went under. There was no special administrative regime in place but there was the UGC, with all its flaws, which was certainly not keen to see institutional failure.

It does suggest that no matter how bad things get there is an institutional course which can be followed which leads to some form of successful future. Market exit is far from the likeliest outcome.

Avoiding the difficult choices

A very clear description of the events of 40 or so years ago is provided by John Sizer(1). He offers a detailed analysis of how the UGC and universities were ill-prepared for the cuts and suggests that the sector had not

faced up to hard choices in the allocation and redeployment of resources between universities and within universities, partially because throughout the 70’s Senates exerted a dominant influence at the expense of that of Councils.

Sizer includes case studies of nine universities which are largely, but not wholly, consistent with the view that by May 1979 the UGC and the universities were responding to short term resource reductions and not really addressing longer term planning or recognising those tough resource allocation issues.

It is instructive to see the subsequent success of these case study institutions (admittedly using the crude lens of university league table performance) and some of the others which experienced more or less severe cuts in funding from 1981 onwards.

Back in 2020 in the first months after the beginning of the Covid Pandemic it felt that the challenges faced by institutions were the most severe they had been since 1981. In 2025 though it is reasonable to say we hadn’t seen anything yet. The sector is now in a position which feels even closer to where it was in the early 80s than at any other time.

Failing to plan

Judging from Sizer’s general observations and the insights from the case study institutions there was no real action taken by anyone before the big cuts were announced. There appeared to be a generally held view, both in the UGC and in universities, that even with the huge national economic difficulties of the late 70s that somehow the UK sector would still get roughly same amount of money as previously.

Sizer observes that letters to universities from the UGC in August and October 1979 gave indications of the likely direction of travel – no increase in funding at best and the introduction of international fees. Universities were asked to consider three scenarios – a modest increase, flat funding and some decrease in funds – but the advice was unclear. In any case the UGC misread what was coming as did universities: the worst case scenario they were asked to plan for was a 5% cut and this was not taken terribly seriously by anyone it seems.

The introduction of fees for international postgraduates (who made up over a third of all postgrads) and the withdrawal of subsidies for them was expected back then to have a similar impact as the current crisis in international student recruitment is likely to have on universities today. Those with large international student populations needed to work out how to sustain or replace the lost income. It appears this really didn’t happen either. As Sizer notes:

There is little indication of any sophisticated analysis of the financial and resource implications; none of the universities employed computer based interactive financial planning models. Whilst the extent of the discussions by Senates and Councils varied between universities, in a number of instances it appears to have been non-existent or limited. Some further actions were taken to restrict future expenditures, but the need to develop financial contingency plans in anticipation of possible financial reductions appears not to have been fully recognised.

In October 1980 Sizer reports that Dr Edward Parkes, UGC Chair, addressed the the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals (CVCP, now UniversitiesUK) and warned that cuts were likely along with more direct intervention by the UGC in the affairs of individual universities than hitherto. He added that there would also be a need for more collaboration between universities and at a time of declining resources “a philosophy of laissez-faire with regard to the development of all but the most expensive subjects could no longer be sustained.”

Parkes also stressed from a political perspective, “universities not only had to adapt themselves to new needs and new tasks, which in fact they had always done, but they must be seen to be doing so.”

Although since the demise of the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) there is nothing analogous, in England at least, to an agency with the powers of the UGC (the OfS, whilst it wields considerable power is a bit different and is a regulator rather than a planning body), the parallels with the current situation are striking.

By the time of the March 1981 White Paper forthcoming reductions in spend were estimated by CVCP to be up to 15%. But some still did not heed the warnings and, according to Sizer, with the arrival of the 1 July 1981 grant letter:

Whilst the UGC can be criticised for failing to give a clear indication of the range of possible cuts…the primary responsibility must fall upon the management of universities. Management implies making and implementing decisions under conditions of risk and uncertainty. Failing to prepare contingency plans cannot be justified simply on the grounds of uncertainty about the likely content of the UGC’s 1st July grant letters.

It really does seem that universities, individually and collectively, failed to recognise the scale of the challenge, did not prepare or plan and were simply not in a position to navigate a route through and respond to the very real reductions in funding.

Bad, but not that bad?

Shattock and Berdahl, in their piece on the history of the British University Grants Committee(2), conclude with the scathing criticism that by 1979 the UGC was in a mess:

Its planning mechanisms were in tatters, with the Chairman being able to do little more than react to the twists and turns of the Government’s counter inflation policy. It had sought with some success to keep the universities informed of developments but there could be little pretence that it remained a body which carried much weight with the DES [Department of Education and Science] or in Whitehall.

Not much help therefore for universities facing large financial challenges.

A report of a 1984 Symposium(3) considering the effects of the cuts several years later indicates some of the issues which remained but was notable for its observations that things were perhaps not that bad. Universities survived although some courses had closed and staff…

…even in areas where student numbers have been reduced or applications discontinued, are teaching more hours and facing larger classes. But the cataclysmic events forecast by many have not happened. The situation as a whole seems remarkably normal, almost as if 81 had not happened.

Alan Waton, one of the authors, notes that the AUT (the Association of University Teachers, the academic staff trade union) sought mainly to protect jobs and that eventually there were almost no compulsory redundancies. Given the level of redundancies currently being reported across the sector, although mainly voluntary it seems at this point, things may yet get worse than the out-turn from 1981.

In the Autumn of 1981 Peter Swinnerton-Dyer, University of Cambridge Vice-Chancellor, and future Chair of the UGC, writing in the London Review of Books, made a number of points which, over 40 years on, have some resonance with our current position. He covers a range of topics including the shift away from research towards teaching (and the subsidy of the former) and the consequences of financial constraint in terms of the “gradual collapse” of scientific research in some universities (perhaps rather overstated) as well as the ending fee subsidies for international students and the Robbins principle. But the really interesting comments are about the response of some in the sector to the huge financial challenges faced and the view that the best thing would be to wait for a change of government and the restoration of finances rather than planning to respond to the new realities.

Things are a little different today in that the government has changed but the reality hasn’t. The attitude of some identified by Swinnerton-Dyer though undoubtedly still exists:

They believe that the way to minimise damage to the university system is to carry on all our activities as usual, and to react to external pressures as little and as late as possible: that policy will avoid unnecessary sacrifices and may lead to the cuts imposed on the system being smaller than they would otherwise have been.

It does seem that back at the beginning of the 1980s then, despite the huge financial issues looming, many universities were slow to respond other than with short-term actions to address the immediate cuts rather than planning for the longer-term changes needed to plot a course through what was going to be a radically different environment.

Where we are now

Some would argue that we are in a not dissimilar position now and that institutions have not responded sufficiently rapidly to what was inevitably going to be a huge financial challenge. Characterising it very simplistically you could suggest that while some back in the early 80s were waiting with fingers crossed for a change in government, the more recent stance has been to build in over-optimistic projections of international student recruitment. The effect is the same though, with the difficult decisions about changes required to deal with the new financial realities postponed. Now that is not the case with every institution of course but it does seem that many are not prepared for the worst-case scenarios, we aren’t ready for closer collaboration across the sector and not everyone is able to respond nimbly to rapidly changing circumstances. Above all though institutions need to determine that they are not avoiding necessary difficult decisions by waiting for a rescue operation that may never arrive and that they are willing and able to take control of their own destiny.

Whilst it is the nature of the market, societal trends, government policies (particularly in relation to international students) and the avoidance of difficult decisions nationally about the funding of higher education which have landed the sector in this place rather than the determination by a national agency of the distribution of cuts, the effects are not dissimilar. And although the capacity and capability of the various national agencies to help institutions is extremely limited there does appear to be a genuine willingness towards and acceptance of the need for some form of collective action.

Even so, there remains an obligation on institutions themselves to act to ensure their long-term sustainability.

A long-term effect

The decisions taken now will have profound long-term effects. As the impact of the 1981 cuts shows, short-term difficulties need not be an obstacle to ultimate success. Some institutions which were hit particularly hard in the early 80s nevertheless came out of it all in good shape. Others appear not to have been so fortunate but they did all survive and progressed, at least partially. There will, of course, have been a multiplicity of factors impacting on the growth and development of these universities over the years but it does seem that some have managed to achieve more than others, at least in the domains which contribute towards domestic university rankings.

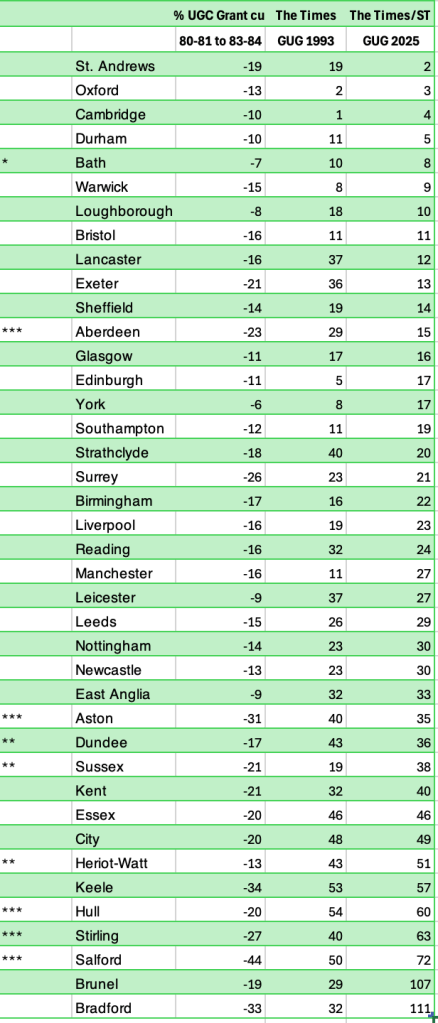

The following table shows a selection of universities which were subject to cuts in 1981, some severe, other less so. Universities are ranked by the size of the cut they faced. Student number growth from 84-85 to 22-23 is also shown

This table shows the cuts from most to least severe. Sizer’s nine case study institutions are highlighted here and he categorises them as follows:

* Treated relatively well by UGC cuts

** Middle Range

*** Relatively harshly treated

One other piece of data, not shown here but worth noting, is that everywhere, with the exception of the University of Bath, shrunk student numbers or stayed roughly the same between 1979-80 and 1984-85. The student number growth since then though is pretty spectacular with most universities increasing their numbers at least four- or five-fold in the four decades since the cuts.

Table 2 shows the same universities and their subsequent placings in the Times University Rankings of 1993 (the first year the league table was produced (5)) and 2025. Institutions are ranked here in order of their placings in The Times/Sunday Times Good University Guide 2025 and it does seem that some universities which faced the deepest cuts, have not enjoyed the same success (in the rankings at least) as some others. It is far from a consistent picture though with some, such as Aberdeen and St Andrews, seeming to progress pretty well.

The big takeaway from all of this is that these universities, even those which faced the biggest cuts from 1981 onwards, by and large survived and thrived. Things are bad now but with all the talk of institutions going bust it is worth remembering that we have been here before, it was difficult, but no institutions went under.

This is not complacency but simply to acknowledge that it is possible for universities and colleges to navigate through this. It’s hard to do it alone but with support from each other, from UniversitiesUK, sector groupings, governing bodies, banks and the regulatory agencies, it can all be worked through.

Looking to the future

Whilst there are then some notable similarities between the major difficulties faced by universities back at the beginning of the 1980s and the significant financial challenges institutions are facing today, the sector is a very different one now. Decisions taken, albeit in some cases belatedly, by institutional leaders will have significant long-term impacts – on the staff who might be losing their jobs, on the future sustainability of those organisations and, potentially, on the national position of some academic subjects. In a much more marketized environment and without a central planning agency, where demand does not exist it is difficult for institutions to sustain subjects which struggle to recruit students or are not bringing in much in the way of research income.

Once a subject closes at an institution, particularly in the sciences, it is very hard indeed to re-open. It might not be in the national interest if the lack of student demand for a particular hard science makes it seem unviable at one or more institutions but no-one is taking this kind of strategic subject view. The OfS, as per its remit, is focusing on the consequences for students. So even if there are no market exits, there may be disciplinary realignments and retrenchments which have undesirable long-term impacts.

Arguably, institutions are now even more important anchors within their communities than they were 40 or so years ago. Back then there were other big employers with big economic impact, prominent in cities and communities. Now universities and colleges are much more central and their loss would therefore be much more profoundly felt. Moreover, institutions have a critical role to play in society more broadly, not just research and education contributions but also their essential place the social and cultural fabric of the nation as well as, crucially, in economic recovery.

Of course where we are now is very different from where we were in 1981 but there are some strong parallels and some important lessons to be learned not least the need for clear-headed longer term planning, real collaboration between institutions. A joined-up response to government is important too as is reinforcing the central role of higher education institutions to the social, economic and broader prosperity of our country. We’ve got a long way to go but there are grounds for optimism about the future. And institutions have a lot they can do themselves to shape their own destinies.

References

(1) Sizer, John ‘A Critical Examination of the Events Leading up to the UGC’s Grant Letters Dated 1st July 1981’ (Higher Education, Vol. 18, No. 6 (1989), pp. 639-679).

(2) Shattock, M L and Berdahl, R O: ‘The British University Grants Committee 1919-83: Changing Relationships With Government And The Universities’ (Higher Education, Vol 13 (1984), pp 471-499)

(3) Reid, I., Brennan, J., Waton, A., & Deem, R. ‘The Cuts in British Higher Education: a symposium.’ (British Journal of Sociology of Education) 5(2), (1984) 167–181.

(4) Swinnerton-Dyer, P. ‘Prospects for Higher Education’ (London Review of Books, Vol. 3 No. 21 November 1981) https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v03/n21/peter-swinnerton-dyer/prospects-for-higher-education

(5) With thanks to John O’Leary for providing the Times league table data from 1993.

Leave a reply to in denial – left to my own devices – occasional thoughts on higher education Cancel reply