Not a pretty picture

The Office for Students (OfS), the principal regulator of higher education in England, has just published its latest annual financial sustainability report. It’s not a pretty picture:

Data published today shows that levels of surplus and liquidity are expected to decline across the sector, with 43 per cent of institutions included in the analysis forecasting a deficit for 2024-25. This contrasts with last year’s forecasts made by institutions, which suggested an improvement in financial performance for 2024-25. The primary reason for the deterioration is lower than anticipated levels of recruitment of international students.

Despite the current hugely challenging scenario, the optimism expressed by universities about the future is striking with significant growth in both home and international students included in forecasts. This does not feel realistic and, as the press release puts it:

If these optimistic projections are not achieved, the deterioration in financial performance for the sector will probably continue in future years – unless significant reform and efficiencies are delivered.

I’ve written here recently about the risks of disorderly exit of UK universities and the responses which might be considered to prevent this. The BBC’s piece on this issue has a couple of interesting quotes from Susan Lapworth on the issue:

Susan Lapworth, chief executive of the OfS, told the BBC it was “not currently expecting any large or medium institutions to fail over the next 12 months or so”.

She said: “Many institutions are financially secure or taking sensible steps to ensure that they’re financially secure, so I wouldn’t want students to be unduly concerned about these issues.”

But she went on to say that the OfS was working with a small number of institutions that were “under real pressure”, including ensuring they drew up plans to protect students in the event that they were forced to close.

So, under this analysis, we might be ok for a wee while then in terms of institutional collapse. A helpful summary of the report overall is provided on Wonkhe by Debbie McVitty and she highlights the points made about over-optimism in institutional forecasts of growth in both international and UK student recruitment.

But universities and colleges are under significant financial pressures and the OfS, whilst it is able to monitor the position and support conversations with stakeholders, is not empowered to step in to support what are, after all, autonomous institutions. Given all of the challenges and the excessive optimism of many future student number projections it really does feel that some form of special administration regime is required to prevent the disorderly exit of a university.

Under pressures

The report also contains a handy list of some of the major financial pressures universities are under at the moment; some of those which are affecting financial sustainability include:

- High levels of variability in student recruitment

- Continuing decline in the real-terms value of the UK undergraduate tuition fee

- Inflationary and economic pressures on operating costs,

- The overall higher education financial model

- External influences on the international student market

- Cost of living challenges for students and staff,

- Increasing backlog maintenance and strategic capital investment needs;

- A lack of certainty in the future funding and economic environment,

- The importance of the role of banks and other lenders in provider financial viability,

The fifth bullet here notes the possible impact of external influences on international student numbers on which many institutions are depending in terms of future financial sustainability.

One of those influences is the Government’s immigration white paper published on 12 May. It proposes a number of concerning changes for universities including a tightening of what already feels like an extremely rigorous UKVI regulatory regime but also a shortening of the post-study graduate work visa route from two years to 18 months and, bizarrely, a new levy on institutions relating to their income from international student recruitment which will, apparently be “reinvested into the higher education and skills system.” Leaving aside the financial impact of this extraordinary new tax on cash-strapped universities, it is possible that the impact of the changes to the visa regime and graduate route, when combined with the overall tenor of the anti-immigration rhetoric in the white paper, will negatively affect international student recruitment in the years ahead.

This is critical given the increasing dependence on that income from international students. As the OfS report notes, by 27-28 almost half of fee income and over a quarter of total institutional income is forecast to come from this source:

In 2023-24, international fee income accounted for 45.6 per cent of total higher education fee income and 23.4 per cent of total income. This has increased from 45.1 per cent of total higher education fee income and 23.2 per cent of total income for the sector in 2022-23, and is predicted to rise to 48.9 per cent of total higher education fee income and 26.3 per cent of total income by 2027-28.

How the immigration white paper impacts on this is therefore a crucial element in financial sustainability.

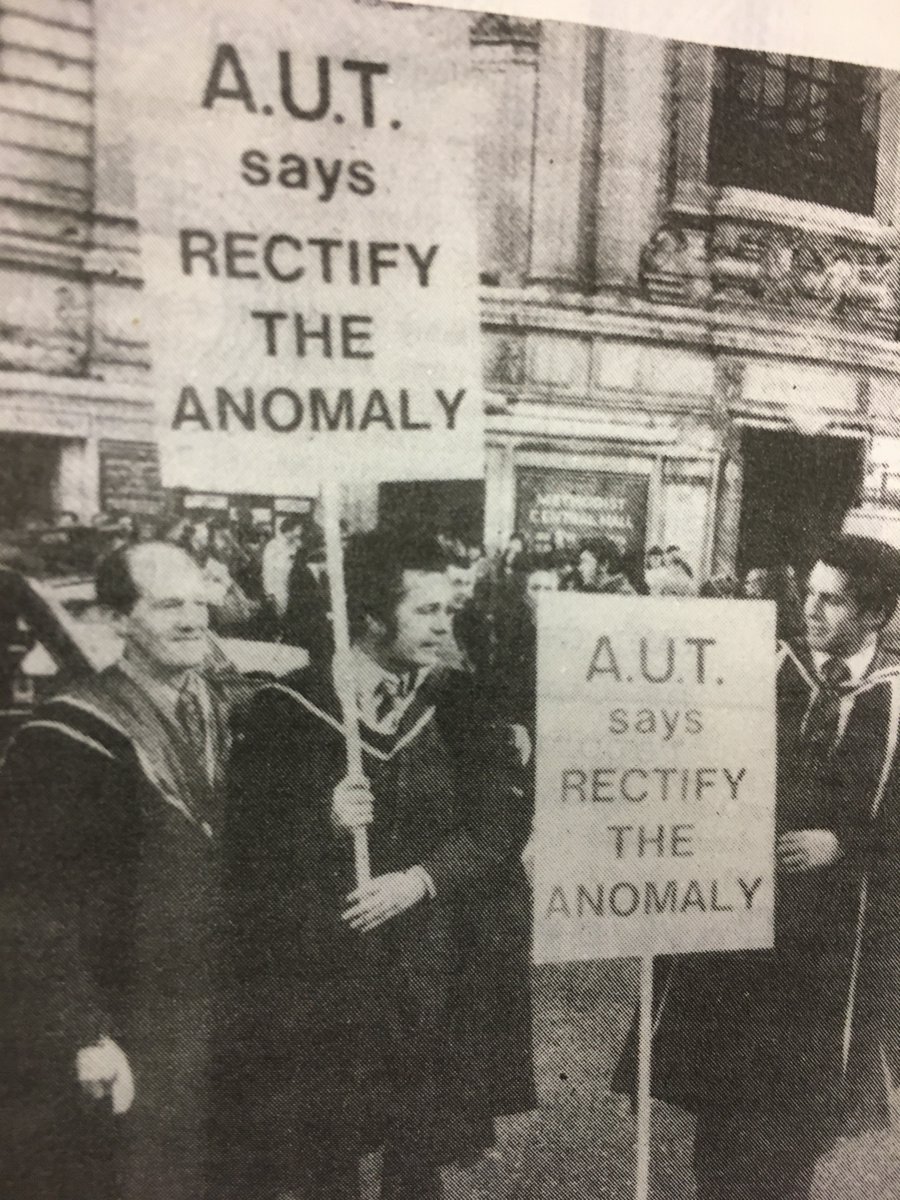

Rectify the Anomaly!

This was, famously, the world’s most erudite and least effective campaign slogan. Coined by the Association of University Teachers (the predecessor of the University and College Union) during a campaign in the mid-1970s when university staff were the only group (hence the anomaly) to miss out on a pay award because of the timing of a new piece of pay control legislation, it did not have the desired effect.

We are unlikely to see placards with slogans demanding a Special Administration Regime, no matter how snappy it may sound, but this is now becoming a critical issue for the sector. It does seem though that there is something of a consensus around the need for such a model.

Public First, in a paper published in 2024 and covered here, suggested there should be some kind of special administration regime with an education administrator appointed to support universities on the verge of collapse.

This seems to me to be very much the last resort though and a prior part of any special administration regime should be a taskforce (comprising a mix of sector experts and external specialists) which would be sent in to keep the show on the road, address the immediate financial challenges and begin to set out the organisational changes which are required and maintain confidence among all stakeholders. Agreement by the governing body to this approach would be a pre-condition for accessing any emergency funding from government which might be made available.

Debbie McVitty, in her summary of the OfS report, quotes Philippa Pickford, Director of Regulation at the OfS, who said in the press briefing:

OfS has now said that it is talking to government to put forward the view that there should be a special administration regime for higher education.

It is positive that the sector’s regulator is also arguing for this but it also shows how limited the OfS powers actually are. Whilst they can offer some support to institutions on the brink, in reality they are, like many, just observers of the unfolding problems.

Standing on the sidelines

The OfS does have a lot more information and is therefore able to comment more authoritatively on the data but the regulator is still not empowered to do much more than stand on the sidelines and does not have the remit to do much more than monitor the situation. So what other observations of note appear in the report?

First, some good news:

Through our monitoring activity, we’ve seen increasing numbers of providers taking action to manage financial pressures, including protecting their liquidity through cost management, boosting student recruitment and strategically assessing their asset base. There are some instances of more strategic cost reduction plans being implemented to manage costs proportionate to income.

This activity has made an impact and as a result we saw better than forecast aggregate financial performance and liquidity in 2023-24, albeit reduced from the previous year.

But there has been a need to monitor more and talk to more people:

During this year we have increased our monitoring activity and engagement with the sector and individual providers. We continue to build our understanding of how risks are materialising and how providers are responding, to inform our ongoing work with those experiencing financial difficulty.

We also continue to engage with banks, lenders and other organisations on these issues.

Unfortunately though, it really doesn’t go much further than this development of a better picture of how bad things are and talking to students and others:

We are building a greater understanding of the aggregate impact of the changes providers are making in response to financial challenges. We regularly talk to providers about changes that they are undertaking. We are also engaging with students to hear about the ways their experiences are being affected, and with other stakeholders to understand a wider range of changes. This will help us to understand where risks to provision and students’ experiences may emerge and how these can be mitigated. It also helps us to identify changes to the size and shape of higher education provision. We will work with the sector as we develop this bigger picture.

This is good, and not unimportant, but it is not going to create the conditions for financial sustainability for all. The key point is that institutions are autonomous and have to make their own decisions:

The OfS does not have the power or remit to intervene in these decisions, but we will act to protect students’ interests where there are significant risks to a provider’s sustainability. This could range from convening discussions with experts on financing arrangements to ensuring effective communications with students.

The powers of the OfS really are very limited in this domain. Which is why they and others are proposing the introduction of a special administration regime. This will allow everything to move beyond monitoring, understanding and discussions to taking action to address the challenges.

Build and they will come

The OfS is, rightly concerned about the extent to which institutional and hence sectoral improvement in financial outlook is based on increasing student numbers and notes the impact of variations in recruitment across different institutions in the most recent cycles. In particular:

The overall changes in UK student recruitment, particularly the increases in recruitment by larger and higher tariff providers are likely to be a direct response to the failure to achieve the forecast non-UK recruitment. It demonstrates that changes in non-UK student recruitment patterns can affect all providers, directly or indirectly.

At an aggregate level, providers have estimated that UK and non-UK entrant numbers will increase by 140,614 FTE (26.0 per cent) and 58,610 FTE (nineteen point five per cent) respectively between 2023-24 to 2027-28. Providers have forecast that full-time FTE undergraduate entrants will increase by 25.2 per cent (124,141 FTE) between 2023-24 and 2027-28. More than 80 per cent of this increase is forecast to be from UK students.

This is pretty staggering. Across the English sector, institutions are planning that almost 200,000 extra home and international students will be recruited. That is about the equivalent of eight decent sized universities. Given all of the steps that institutions are currently taking to cut costs, including making staff redundant, it feels more than a little impractical to plan for growth at such a rate.

The other point to note here is the continued expansion of franchise provision where reported net income relating to contracted-out activity increased by nearly 32% between 2022-23 and 2023-24. For those institutions which report on this their income from contracted-out activity is forecast to increase by a further 16.5 per cent by 2028-29.

A small number of universities and colleges have really gone big on franchising and this has raised concerns recently where some of the partnerships established by some institutions were shown to be failing to deliver good outcomes for many of their students. The continued growth in this area is likely to attract increased scrutiny from the OfS I suspect.

Forward to the SAR!

It is encouraging that the OfS is arguing for the introduction of a special administration regime. I do think this does have to happen sooner rather than later. Whilst Public First, which set out such a proposal last year, suggested that legislation may be required for this to happen, it is not clear to me that this is the case. If co-operation with regulatory intervention and allowing a team appointed under a special administration regime are set as pre-requisites for accessing the government funding necessary to keep an institution afloat then this should be sufficient to enable the necessary involvement.

This really has to be put in place soon. We can’t wait until the reforms promised in the post-16 white paper later this summer. By then it might be too late for some.

Leave a reply to dennisfarringtonc28aa93dcd Cancel reply